Sustainability: Corporate Ambition, Governance, & Accelerated Delivery

The imperative for global action to tackle climate change is clear and the pharmaceutical industry has a key role to play. Governments have entered into international commitments to reduce climate impact (carbon emissions) and protect nature (water, land, air, and biodiversity) with policy frameworks established to facilitate and drive progress against agreed targets.

As emphasized at the recent UN Climate Change Conference COP27 (held at the end of 2022 in Sharm el-Sheik, Egypt), international focus is now on implementation. Supporting standards for science-based targets are available and being refined to help organizations measure and manage their environmental impact.3, 4 Most companies have some existing initiatives underway, but many do not yet have a fully comprehensive and integrated program.

This article explores effective management and oversight processes for accelerated delivery of large-scale programs of work. Practical challenges of working across multiple organizations and countries are discussed together with the growing expectation for independent audit and assurance of claimed benefits delivery. A collaborative mindset must prevail between pharmaceutical companies, suppliers, and regulators and include strategic partnerships that go beyond the pharmaceutical sector so we can move together to a more sustainable future.

Scope and Scale of Corporate Ambition

Company boards have a duty of service to their shareholders to proactively identify and address key risks impacting their organization. These expectations are defined in various national codes.5, 6, 7 Failure to properly address the topic of environmental sustainability not only impedes wider efforts to address climate change, but also could have a material impact on the company’s business. For instance, in the future, the company might be unable to supply products and services against new and emerging sustainability requirements, lose sales to competitors who are recognized for their superior sustainability performance, or receive financial penalties or fines for noncompliance.

There are also less tangible, but still very important, reputational risks associated with not taking the topic seriously enough, including damaged reputation—making it harder to attract and retain key talent, especially as potential new recruits become more value driven in their choice of employer—and loss of public goodwill and government discretion, which could adversely impact revenues and investment decisions. The risks are equally applicable to both privately owned and publicly traded companies.

Small- to medium-sized pharmaceutical companies, together with suppliers of goods and services, are not typically held to the same governance standards as larger companies. But they will still need to align with their customer requirements, prioritizing environmental sustainability alongside rather than behind revenue generation. Alternative sources of supply may be sought if suppliers cannot meet their customer expectations. A robust discussion will be required for the company board to agree on the level of ambition for their organization.

Environmental sustainability goes beyond continuing conventional energy reduction and waste elimination programs to include impacts on water courses (e.g., antimicrobial resistance), effects of pollution on air quality, and a focus on biodiversity, including preserving and restoring ecosystems. The public and investors expect meaningful and stretching goals (e.g., a time horizon of 2030 is much more engaging than 2050). Future market access for medicines will increasingly depend on sustainability prerequisites being satisfied before being able to supply: for example, risk assessments needed for EU product authorization,8 and performance data accompanying commercial tenders for UK National Health Service.

In response, many companies are introducing a new dedicated Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) scoreboard that will be published as part or alongside the annual shareholder report. Both the company’s carbon footprint (CCF) and product carbon footprint (PCF), which describes the total amount of carbon emissions generated by a product or a service over the different stages of its life cycle, for their highest-impact products should be included in the ESG scoreboard. It is key that sustainability goals are confirmed as achievable before they are published. A meaningful method of reporting tangible progress should also be developed that can be consistently applied over the years ahead. Environmental sustainability programs are long-term (ongoing) initiatives and cannot be reported the same way as shorter-term new product developments, factory builds, or major IT deployments.

Company boards should anticipate some tough internal debate when setting goals. Being bold will require business model tradeoffs such as key investments in new facilities or reformulated products, closing facilities that can no longer meet expectations, and changing suppliers and service providers where needed. Companies are expected to take responsibility for ensuring their suppliers and service providers are aligned with their goals. They cannot abdicate corporate accountability for environmental sustainability by handing over responsibilities to a third party. Rather, companies must ensure what they do is appropriate and proportionate.

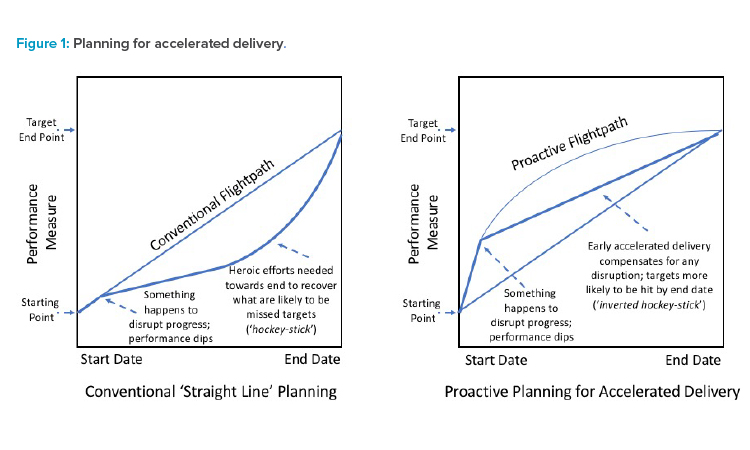

Company boards should expect growing pressure from the public, shareholders, governments, and employees to do more and go faster. Interim targets for end goals should therefore be set to challenge conventional “straight-line” planning (as shown in Figure 1), which will miss the end goal if some unforeseen event disrupts progress unless a heroic effort is made to recover performance (the so-called “hockey-stick” performance profile). It is recommended that an early step-change in tangible performance is sought to accelerate overall delivery so that if some unforeseen event disrupts progress then it is still relatively easy to achieve the end goal performance (an “inverted hockey stick” performance profile) (see Figure 1).

This change in mindset will increase pressure in the business. Company boards can expect some pushback from leaders and managers who will already be consumed with existing business objectives. It is vital to be clear on priorities to mitigate the squeeze on middle management and ensure creative thinking is employed to seek win-win solutions that collectively address improved sustainability performance, quality, and safety alongside other business objectives. Development of a clear decision-making framework will help establish and maintain consistent and ethical priorities.

It is quite possible that, despite best endeavors, companies will not be able to fully realize absolute goals such as net zero carbon or net positive nature. In this scenario, offsets may be required by which the company invests in external initiatives to improve environmental sustainability. Ideally these initiatives will be in the same geographic region and address the shortfall in a particular goal (e.g., investment in forestry developments or water preservation).

The use of offsets has come under some criticism owing to it being perceived as an excuse for not doing more within the business. Therefore, before deploying offsets, companies should be able to demonstrate that they did as much as reasonably practical to directly address parameters under their control. Remember, too, that some offset projects will take many years to come to fruition before a company can claim credits for benefits realized: new woodland, meadows, etc., must mature before they can realize their full potential for carbon reduction, and then these ecosystems must be maintained over the long term to secure and preserve these as ongoing benefits.

Once the company’s strategic goals and the resulting financial implications are understood and agreed upon, a transformation program with supporting governance and reporting can be put in place. The company board should be given a progress report at least annually, and more frequently if there are decision points or escalation items requiring their attention. A suitable scorecard will need to be developed to show progress against strategic objectives comprising a mix of both lead and lag measures.

Company boards should consider having external verification of progress on their environmental sustainability goals rather than relying on internal reporting to avoid claims of “greenwashing” and the damage that can do to corporate reputation. Independent certifications and statements of assurance can then be used in annual company reports to shareholders. External lobby groups and industry benchmarking organizations such as Dow Jones Sustainability Index and Sustainalytics’ ESG ratings will use this and other information released by the company to assess progress. In the future, a common standard comprising a simple set of vital few measures for ESG reporting may emerge. But in the meantime, companies need to align to evolving best practices.

Transformation Program

A transformation program comprising key workstreams and appropriate governance oversight will be needed to deliver on company goals. Consideration should be given to design the workstreams to best fit existing organizational structures, objectives, and priorities. Not all workstreams will trigger new projects; it should be possible to augment existing work.

A central transformation team should be formed that is connected with local business functions and project teams to manage the transformation. The head of that team should have a proven track record of portfolio program management across multiple business units given the potential size of the program. Maintaining strong links with key stakeholders across the business will also be very important. Formal qualifications in program management, such as PRINCE29 or PMI certification,10and leveraging any previously established working relationships will be advantageous.

Some firms have elected to create a central funding pool to resource all related projects, whereas other firms have asked their business to integrate sustainability into their existing business plans. While each approach has its pros and cons, the most pragmatic approach would seem to be a fusion of both. This would help ensure a good balance is struck between local managers having ownership without overwhelming them with a new central program in which they feel they have little influence. Costs should be monitored and benefits tracked so that ROI projections can be affirmed. The CEO and CFO should be fully engaged and support expenditure plans where the total spend over multiple years on environmental sustainability is very large.

Company standards for various aspects of environmental sustainability should be defined in technical documents and procedures that complement Good Clinical Practice (GCP), Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), Good Distribution Practice (GDP), etc. that apply to the scope of activities undertaken by their organization. The quality of pharmaceutical products must not be adversely impacted; patient safety must be protected at all times. And of course, standards and operating procedures should be kept up to date under change control. New and emerging nongovernment organization (NGO) guidance, government legislation/regulations, and other recognized reference standards (e.g., national tender requirements) will also be separately monitored to ensure internal standards remain in compliance.

A training curriculum with supporting technical training courses will be essential to build wider organizational capability. Do not assume existing training programs cover what is needed in sufficient detail. Many new graduates will be very familiar with the latest sustainability developments and expectations, whereas other staff may lag behind what is needed without realizing it. It may be necessary to create bespoke training to meet local needs where standard training materials are not available. Further training may also be needed for management engagement and supportive behaviors. Competence-based functionality and assessments can be provided in training where appropriate to help assure a successful capability build. It may be necessary to hire subject matter experts to develop and maintain these standards and provide technical support in this fast-moving topic area.

Timely and accurate progress reporting will be needed: overall company performance for senior executives, workstream level for program management, and at a local business level. A set of operational key performance indicators (KPIs) should be defined for the transformation program to measure tangible performance improvement and not just consist of progress reporting on program activities. Where possible, the KPIs should link to externally defined measures used by external lobby groups and industry benchmarking organizations.

A subset of sustainability metrics should be selected for integration within business dashboards to promote a balanced and considered view on overall business performance and ensure sustainability does not become viewed as a silo. More specific local business performance dashboards can be developed with relevant measures to track and drive the transformation bottom-up.

The central transformation team should be transparent and escalate poor program delivery and poor performance improvement. Calculations behind performance measures need to be clearly defined and controlled. It is important to recognize that small changes in the math used may simplify internal processes but they can also mean those same calculations become out of sync with external benchmarks defined by independent organizations overseeing industry progress. Care must also be taken to ensure no gaps or double accounting exist in the overall calculation of climate and nature impact in the supply chain. This can be particularly challenging when considering the contribution of third parties who do not yet have the methodology or means to provide accurate figures.

Governance

Overall governance should be kept as simple as possible. Given the significance of environmental sustainability, it will most likely be appropriate to have a new dedicated top-level forum to provide strategic direction and to oversee implementation and delivery of targets. The seniority of the appointed chair of the top-level forum will indicate how seriously the company is taking environmental sustainability (e.g., having C-suite chair would set a clear tone from the top of an organization).

Representatives from R&D, manufacturing and supply, and commercial should all be included at the top-level forum, along with the main functions needed for delivery such as the sustainability group, engineering, procurement, legal, and corporate communications. The quality function must also be engaged where sustainability changes impact product registrations, analytical testing, manufacturing processes, etc. to ensure that the quality, safety, and efficacy of medicines and devices are not compromised in any way. Of course, care must be taken to ensure quality is not used as a change barrier to avoid sustainability improvements where there is no impact on product quality. Stakeholders will need to be fully informed so that they can have robust conversations and agree on the best solution in what are sometimes difficult and challenging situations.

Responsibilities for members of governance fora should be assigned to named individuals. Decision-making expectations and meeting cadence should be clear. More frequent governance meetings should be considered when initially setting up the transformation program and its supporting activities compared to later routine oversight of established work items.

Existing company governance structures and processes can be used to support this new top-level governance, assuming these meetings can give sufficient priority and agenda time to environmental sustainability. Amendments will be needed to terms of reference and membership of governance meetings. New dedicated oversight will be required where exiting governance cannot be leveraged.

Financial impact assessments that test various business scenarios should be refreshed each year, with their output linked into routine business planning. The first intent should be to avoid environmental impacts (e.g., applying new technology or perhaps simplifying a process to remove a problematic step). Consideration can then be given to reducing the environmental impacts that remain. For instance, a company could consider dramatically improving internal circularity to reuse what might otherwise be waste materials.

The quality of pharmaceutical products must not be adversely impacted; patient safety must be protected at all times.

Another example might involve developing symbiotic relationships with other companies for them to use what might otherwise be waste (a “circular economy”), e.g., reusing preheated water between neighboring firms or enabling a critical mass of plastic packaging materials to be collected for reprocessing. Firms co-located in a shared building or on a shared campus might also work together to reduce the environmental impact of communal energy streams. An example of this in practice is the Kalundborg Symbiosis, a public-private partnership between pharmaceutical and other companies in Denmark in which they proactively design their businesses operations to exchange material, water, and energy streams to reduce their expenses as well as their collective environmental impact.11].

A repeating cycle of risk scenarios can be spread over several years—for instance, key products followed by internal operations and then external supply chain—to build up a comprehensive picture that can be shared with the company board. Guidance with supporting templates and tools has been issued by both the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Task Force on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD).12, 13 These assessments provide a vital link that aggregates various company risk mitigation activities into a consolidated report.

Program Management

A holistic and comprehensive program plan needs to be developed to coordinate the various workstreams that span the company. Each workstream may contribute to more than one of the company’s sustainability goals. Detailed plans for each workstream need to be developed with critical paths to capture the rate-determining activities that must be successfully completed. Potential bottlenecks between parts of the organization that should work together will need to be addressed. Organizational silos must not be allowed to impede progress. Plans should be aligned with business plans, with interdependencies identified for proactive management. Roles and responsibilities between the central transformation team and local business units need to be clear. There should be a clear handshake between central and business governance.

Waterfall charts are recommended in order to identify a series of improvement opportunities for each end goal (e.g., reduction in carbon, wastewater reduction, improved air quality, increased biodiversity index). The charts can be used to prioritize opportunities to be implemented within the workstreams and to give confidence that goals will be achieved. Implementation glidepaths for each goal can then be developed for conventional project management.

Supporting KPI dashboards should be developed with lag and lead indicators to track current achieved performance and prospective performance improvements, respectively. Care must be taken to avoid the mix of workstream plans and waterfall charts becoming too complex, as this will impact the ability to effectively maintain them. It is important to be able to drive delivery and maintain momentum of the overall program.

The central transformation team should also put into place effective risk management processes that acknowledge and leverage local processes and procedures. Introducing a rigid central standard that overrides local practices can cause confusion and lead to a lack of ownership. Guidance on risk assessment should be provided to promote consistent understanding of the significance of risks. Risk logs should be maintained to track progress with risk mitigation. Risk treatment needs to be timely and proportionate to the characteristics of the risk posed, with local risks managed according to local practices.

Interventions will be needed where warning signals of emerging challenges are identified to avoid them becoming problematic. Realized problems should receive an effective root cause analysis with on-time closure of remedial actions reviewed by appropriate governance. Solutions for thematic issues and problems should be shared across the business, recognizing that global plans will require approval by top-level governance and should be tracked to complete by the central transformation team. Escalation items should only be referred to top-level governance if they cannot be resolved at a local level.

Communicating keynote successes will help encourage engagement and support. It is important to select meaningful news items rather than rely on KPI metrics. Stories that are easily shared are best, describing a tangible achievement: for example, zero to landfill for a region or globally, formulations changed to remove impact on endangered species or habitats, and external awards from accredited authorities such as Carbon Disclosure Project certification.

Companies should ensure transparent reporting against established public standards—such as the Greenhouse Gases (GHG) Protocol Corporate Standard, which categorizes carbon emissions associated with a CCF—and high-visibility metrics such as the product carbon footprint (PCF). Both CCF and PCF targets and achievements, together with progress against any nature goals, should be published for full transparency.14

Supply Chain and Supplier Partnerships

It can be challenging to assess and track the climate and nature impact in the value chain that is out of the direct control of a pharmaceutical company due to the numerous parties and processes involved. Attention should initially be given to first-tier suppliers to identify the biggest opportunities upon which to focus improvement efforts. After this, second- and third-tier suppliers can be prioritized where they have a particular role to reduce climate impact and improve nature associated with a finished pharmaceutical medicine.

The influence that an individual pharmaceutical company has on a supplier can be very limited when they represent only a small proportion of that supplier’s business. In these situations, it is worthwhile to engage in collaborative initiatives with other companies that have aligned interests to increase leverage on that supplier (pending compliance with anticompetition laws and suitable confidentiality agreements).

The Ecovadis’ ESG platform—with its standard performance scorecards, benchmarks, and performance improvement tools—is a good example of how many companies are settling on a common approach. The use of such platforms and supporting tools makes processes more cost-efficient for suppliers too, reducing the number and variety of assessments received and progress reports requested from different customers, and for different supplier manufacturing sites related to the same customer.

Strategic partnerships provide another means to help suppliers that might otherwise not be able to access green initiatives. For example, the Energize initiative involving Schneider Electric and 10 pharmaceutical companies is aimed at facilitating access to the green energy market for power purchase agreements for hundreds of small- to medium-sized suppliers that might not otherwise be readily available to them.15 The program is a first-of-its-kind effort to leverage the scale of a single industry’s global supply chain in a precompetitive fashion to drive system-level change.

Environmental sustainability, of course, is just one factor considered when engaging suppliers. Many pharmaceutical companies are integrating sustainability as one of a number of topics—such as human rights and quality, health, and safety—to be evaluated and managed together within an integrated approach. A single supplier audit may cover multiple topics instead of having a separate audit for each topic, and the results of that audit shared within a customer community with appropriate confidentiality. The procurement department will need to work closely with the business, including the quality department and other relevant functions, to understand the consequences of serious deficiencies and agree on action plans.

Some changes can take a long time to implement, especially if regulatory approvals are needed. Ultimately, if a supplier is unable to meet a customer’s sustainability expectations or requirements for another topic, and they cannot address the root cause behind that, then an alternative source might be sought. Care must be taken to ensure selected alternatives do not bring other more pressing problems to the supply chain, such as compromised product quality. Early decisions will therefore be needed on critical supplier relationships so that actions can be completed in a timely manner that does not compromise the pace of overall sustainability transformation.

Culture Change

A shift in organizational culture will almost certainly be required to support corporate transformation. It is our experience that there will likely be a strong pull from the broader workforce in support of company efforts toward environmental sustainability. Indeed, many employees will want to be proactively involved in initiatives. While a company will not want to distract employees from their immediate duties, it is also important not to dampen their enthusiasm and commitment for sustainability.

Many companies are engaging their workforce through tangible activities through which employees can feel that they are making a contribution. A good example is the removal of unnecessary single-use plastics in the laboratories and on-site cafeterias. Another example is restoring land in the immediate vicinity of company building to promote biodiversity and to create walking routes for employees to relax in their breaks (with the added benefit of the well-being these spaces can provide).

Middle managers may be more reluctant to fully engage with a corporate transformation program. They may feel squeezed with too many and changing priorities and environmental sustainability can come across as another item on their growing list. The corporate transformation program needs to ensure business priorities are clearly aligned with sustainability goals, rather than trying to make space for separate new targets. An almost seamless integration of objectives will make a big difference to getting things done. A focus of what really matters each year, and it will change year to year, will be key to success.

Last but not least is the role of senior leaders. They need to lead from the front and not just assign a member of their respective management teams to take accountability for sustainability on their behalf. The corporate transformation office should take time to map out senior stakeholders and consider how to best support them in their company’s journey. Some leaders will be natural champions for environmental sustainability, and others less so. Keeping the company’s sustainability objectives and transformation program simple and straightforward will help engage leaders while establishing a clear roadmap of projected achievements that can be used to illustrate their commitment and success.

Incentive schemes are worth considering for senior leaders, middle managers, and the broader workforce to foster and reward the good governance and practical execution needed for a successful environmental sustainability transformation. Experience suggests that selecting a couple of current KPIs from the ESG scoreboard works well for shared bonuses and can be supplemented with personal objectives used in annual performance reviews relevant to an individual’s role. Pharmaceutical companies can also use recognition events with accompanying publicity to encourage the participation and performance improvements of suppliers. Transparent targets and progress reporting across the supply chain will promote engagement and wider confidence in achieving commitments.

Conclusion

Our industry is committed to the patients we serve. This commitment goes beyond the efficacy, safety, and availability of products to address medical needs to include the environmental sustainability of our business operations and products. Comprehensive action by pharmaceutical companies is required to facilitate the necessary transformation for environmental sustainability.

We hope this article inspires the following considerations:

- Has my company set the right level of ambition to help combat climate change?

- Is corporate governance strong enough to drive progress?

- What can be done to do more and go faster?

This article aims to answer these questions with shared insights and experiences on how to establish and manage successful companywide programs for accelerated delivery of environmental sustainability goals. Such programs will be large and complex, presenting a multitude of challenges to manage. Their smooth running and transition to “business as normal” belies the planning and execution effort to make it so.

Further information on project management to help up set up an environmental sustainability program can be found in ISPE’s Good Practice Guide: Project Management for the Pharmaceutical Industry.16