Global Convergence Opportunities

The regulation of drug shortage prevention has rapidly changed over the past several years due to large-scale, highly visible events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, hurricanes, and geopolitical issues. Efforts to effectively address the complex and multifaceted issues contributing to drug shortages require close technical collaboration and clear communication between the pharmaceutical industry and global health authorities.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw how beneficial global health authority collaboration was in addressing critical patient needs efficiently and effectively. Through working groups, forums, and innovative regulatory pathways, regulators addressed shortages across several regions during the height of the pandemic. This demonstrated how regulatory reliance and collaboration can bring benefits to other regulators, industry, and—most importantly—patients.

Assessment of Drug Shortage Regulatory Requirements

Powerful health authority engagement and sharing of information continues through quarterly meetings of the Global Regulatory Working Group on Drug Shortages, which is chaired by the US FDA and includes members from Australia Therapeutic Goods Administration, Health Canada, European Medicines Agency (EMA), Japan Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, and the World Health Organization (WHO).1

Additionally, we are seeing how the EMA is working to improve sharing of information and harmonization of expectations across the member states to improve supply chain resiliency measures.2 We greatly appreciate the ongoing commitment to ensure continuous supply to patients worldwide and would like to provide support from industry to further augment these efforts.

Although regulator collaboration on drug shortage prevention topics has continued, substantial market-specific requirements have been or are being introduced and even expanded. The rapid pace of extending requirements developing in parallel across multiple geographical markets has generated nuanced differences in drug shortage definitions and approaches, reporting expectations, and risk management planning. As a result, ISPE formed a Global Convergence Opportunities team within its Drug Shortages Initiative to assess trends across evolving drug shortage–related requirements and to identify opportunities to harmonize definitions and approaches across markets.3

The corresponding assessment regarding drug shortage regulatory requirements was performed with a global lens, and the convergence proposals presented herein are based on the common themes observed. We believe considering convergence proposals specific to drug shortage prevention activities is important because global convergence can allow faster reactions to disruptive events and thus can correspondingly increase patients’ accessibility to medicines. Specifically, convergence could:

- Increase the reliability of predictive modeling to provide more reliable global demand forecasts and supply resiliency vulnerability information

- Create efficiency in mitigation or prevention activities with meaningful and consistent data for regulators or stakeholders to analyze

- Ensure shortage risk mitigations are developed with optimal global outcomes

- Direct focus on risks to lifesaving/life-sustaining products to ensure balanced investment in risk management planning

- Support greater interaction between regulatory agencies and government bodies by having common terminology and timescales

The following presents a summary of the ISPE Global Convergence Opportunities team’s work. It is to be considered as a starting point for further discussion across industry and regulators on drug shortage prevention regulatory requirements that could be optimally harmonized. It includes approaches to provide a holistic framework worldwide.

Regulations regarding product discontinuations were included because discontinuations can generate or exacerbate drug shortage events, especially if a product is discontinued unilaterally by one supplier. The reported findings consider the regulations, guidance, or draft regulations in place during the authoring of this article. However, regulations can evolve and might have changed since this article was prepared. Manufacturers are responsible for monitoring evolving regulatory requirements and remaining compliant with current global health authority expectations.

Survey Methods

The ISPE Global Convergence Opportunities team consisted of members from the ISPE Regulatory Quality Harmonization Committee (RQHC) and the ISPE Drug Shortages Initiative (DSI) Team. Global market drug shortage and product discontinuation requirements were obtained by surveying ISPE Affiliates in the following regions: Asia Pacific (APAC); Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (EMEA); Latin America (LATAM); and North America. Where possible, the respective documents were translated to English and all markets surveyed are listed in Table 1. The survey consisted of the following questions, and responses were based on health authority–specific guidance and regulations.

Survey questions

(Responses based on local available guidance, regulations, etc.)

Within your market:

- Is there a definition for “Critical Medicines”?

- Are there certain products for which shortages must be reported?

- Is there a definition for “Drug Shortage”?

- What is the required timeframe to report supply disruptions?

- Expected (anticipated, foreseeable, etc.)- report timing in advance

- Unexpected (actual, unforeseeable, etc.)- how quickly to report

- Timeframe to Report Resupply Updates

- What is the required timeframe to report product discontinuations?

- Expected (anticipated, foreseeable, etc.)- report timing in advance

- Unexpected (actual, unforeseeable, etc.)- how quickly to report

- Are risk management plans required to support product availability?

- Are there requirements for stockpiling/safety stock?

- Are there certain products which must be stockpiled?

- What volume (quantity or timeframe) is required?

| Region | Country/HA Surveyed | Total/ Region |

|---|---|---|

| APAC |

| 16 |

| EMEA |

| 18 |

| LATAM |

| 7 |

| North America | Canada United States | 2 |

| Other | WHO | 1 |

| Total | 44 | |

Workshop

After collecting the market-specific data, the ISPE Global Convergence Opportunities team conducted a workshop to assess the survey results. The workshop was structured as four groups consisting of three to four industry experts. Each group was assigned to assess a subset of the collected information with the following set of starter questions in mind:

- How many countries provided relevant information to the topic area?

- Of the countries with requirements, what were the extremes in expectations (e.g., lowest requirements/highest expectations to comply with)?

- Is there anything notable (similarities vs. differences) observed between the major markets (Canada, China, EU, Japan, USA) requirements?

- Were there relevant differences observed between most of the world and major markets?

- Are there any other standout observations the group would like to share?

Survey Results

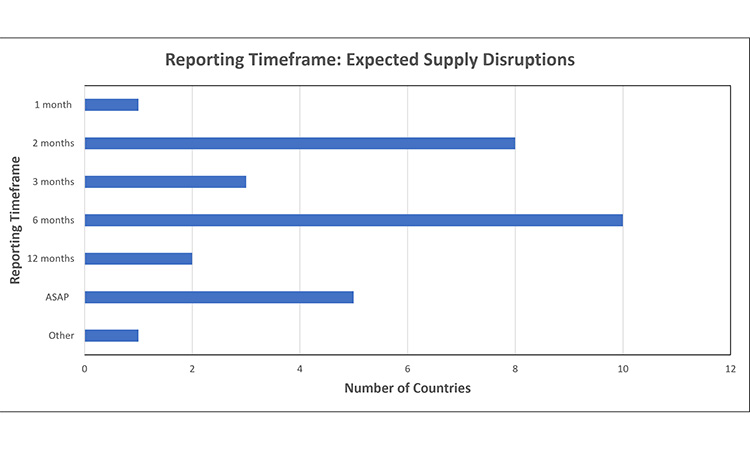

At the conclusion of the survey, a total of 44 markets, including the WHO, had guidance or regulations related to drug shortage prevention, definitions, approaches, risk management, and stockpiling and/or safety stock. Based on this work by industry leaders and subsequent reviews by the ISPE RQHC and ISPE DSI, six themes emerged for convergence exploration: product prioritization, drug shortage definitions, shortage reporting timeframes, permanent product discontinuation reporting timeframes, requirements for risk management plans (RMPs), and requirements for stockpiling and/or safety stock.

Because requirements are rapidly evolving, these results provide only a snapshot in time, and requirements may be superseded by the time of publication. Guidance or regulations related to drug shortage prevention, definitions, approaches, and/or risk management were reviewed through Q3 2023. Due to the increased dialogue around local stockpiling and safety-stock expectations, a subsequent survey was conducted in Q1 2024 to assess current expectations and volumes.

Theme 1: Product Prioritization

Critical Medicine Definition Themes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | No or limited alternative therapies | Medical Necessity | Impact to Widest Population |

Australia | X | X | X |

Canada | X | X | X |

China | X | X | X |

EMA | X | X | X |

Germany | X | X | X |

Spain | X | X | X |

USA | X | X | X |

Brazil | X | X | X |

Chile | X | X | X |

Colombia | X | X | X |

Ecuador | X | X | X |

Austria | X | X | - |

Belgium | X | X | - |

Czech Republic | X | X | - |

France | X | X | - |

Japan | X | X | - |

United Kingdom | X | X | - |

Greece | X | - | X |

Ireland | X | - | - |

Portugal | X | - | - |

Argentina | X | - | - |

Indonesia | X | - | - |

Hong Kong | - | X | - |

Lithuania | - | X | - |

Peru | - | - | X |

Mexico | - | - | X |

WHO | - | - | X |

Total | 22 | 19 | 16 |

Key:

- X (included)

- - (omitted)

Notes:

- Argentina: There is not a formal definition from ANMAT, but Disposition 2038/17 requires approval of the product discontinuation by ANMAT if it is a product containing a unique molecule (API) in the market.

- Canada: no formal definition, but Health Canada has definition and criteria for: critical shortage impact.

- Indonesia: No regulation to notify drug shortage, but if the product is the only medicine in the market, then it is the MAH's decision to notify the BoH.

Table 2 shows the markets which define critical/ essential medicines, and the inclusion of these concepts in definitions per market.

We assessed markets which have established a definition for critical or essential medicines. We observed similar criteria defining a critical/ essential medicine across markets, with the most common concepts below:

- No or limited alternative therapies

- Medical necessity

- Impact to widest population

Of these three, the most prevalent was “no or limited alternative therapies”, followed by “medical necessity”.

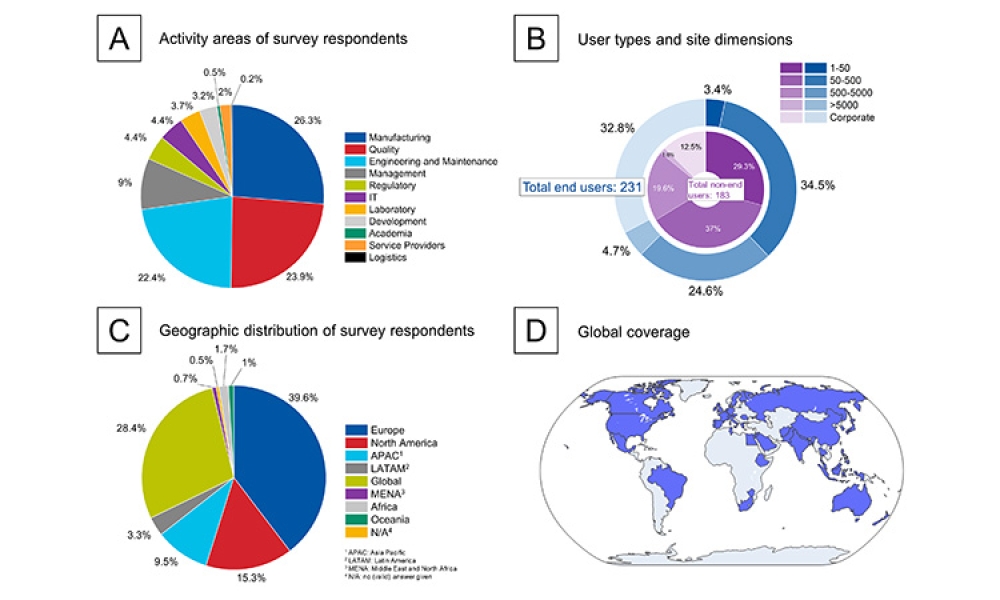

Figure 1: Reportable Product Types7, 12,13, 15, 16, 17, 20, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50

Prioritized Subset= required reporting for specific products including but not limited to: medicines based on Health Authority (HA) list, registration type, medicines meeting local definition of medically significant, no alternatives, etc.

Note: EMA requires reporting for all medicinal products registered under centralized procedure.

Centralised procedure is required for human medicines containing a new active substance (for HIV, AIDS, cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, autoimmune or other immune dysfunctions, viral diseases); medicines derived from biotechnology process (e.g., genetic engineering); advanced-therapy medicines (e.g., gene-therapy, somatic cell-therapy or tissue-engineered medicines); orphan medicines (for rare diseases); veterinary medicines (for use as growth or yield enhancers). It is optional for other medicines containing new active substances for indications other than those listed above in required; significant therapeutic, scientific or technical innovation; or whose authorisation would be in the interest of public or animal health at the EU level .51

We observed that the scope for reporting is almost universally finished drug shortage product. Markets may require all finished packaged products or a prioritized subset of products to be reported. To further assess trends, we grouped countries into these two categories:

- All finished packaged products to be reported (regardless of therapeutic significance) or

- A prioritized subset of finished packaged products to be reported.

- markets that have an established HA list of products to report against;

- may be specified by registration type (e.g., only centralised procedure products, etc.);

- locally defined ‘medically significant’ products;

- products which do not have alternative/ therapeutic equivalent, etc.

- As a unique requirement we found, tender bids may be considered a reportable product type in certain markets.

Most markets require reporting for all products.

Of note at the time of review, two countries have expectations for reporting shortages of API that is used in HA-deemed critical products, in addition to finished goods.

Theme 2: Drug Shortage Definitions

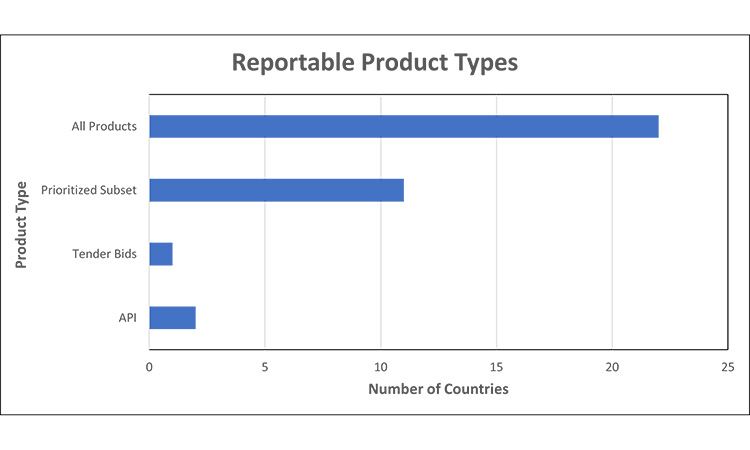

Figure 2: Themes in drug shortage requirements (definition themes)7,11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 20, 30, 32, 35, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 48, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61

Based on local drug shortage definitions, the criteria for a reporting a “shortage” are significantly different across markets and varied based on the perspective of supply vs. demand/ patient needs, reason for the shortage (temporary or permanent discontinuation), reporting of anticipated and/or actual supply disruptions, inclusion of a time element (e.g., defined time or undefined).

- Several countries include both anticipated and actual supply interruptions as part of their drug shortage definition.

- A few markets consider temporary or permanent discontinuations under the “drug shortage” umbrella, while others do not distinguish these as reasons for a products absence or classify permanent discontinuations separately with their own set of reporting definition and timeframes.

Theme 3: Shortage Reporting Timeframes

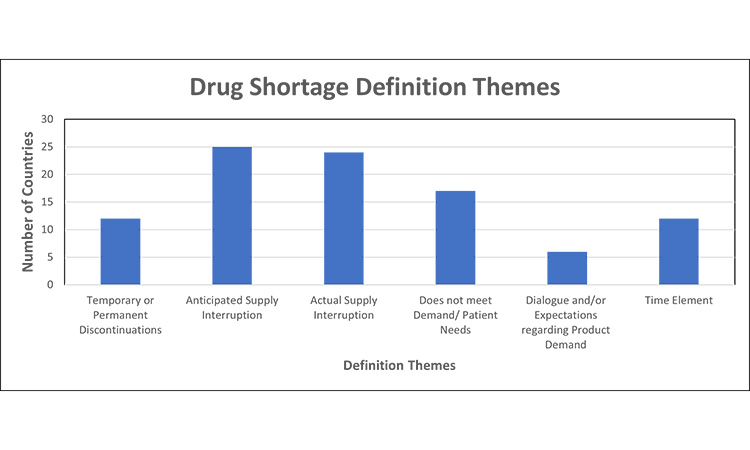

Figure 3: Reporting timeframe trends: expected supply disruptions 7, 11, 15, 16, 24, 30, 32, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 48, 52, 53, 55, 56, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65

Report expected disruptions 1-12 months in advance of event

- Other: Depends upon product priority [Ireland (Low Impact: 1 month | Med-High Impact: 2 months)]

- ASAP: Timeline undesignated, or report within 5 days of identification

- Undefined: No established timeframe for expected disruptions

Note: CP reported to EMA, national products may require 27 different, individual reports, for 1 MAH.

The timeframes to report an expected supply disruption varied from 1-12 months in advance of an event. Within this range, the most common timepoint by far was 6 months in advance.

- One market defines the required timeframe based upon the products’ priority. For example, in Ireland, a product classified as ‘med-high impact’ must be reported 2 months in advance of an event, whereas a ‘low impact’ products reporting timeframe is 1 month.

- Few markets require that an expected disruption is reported as soon as possible or within 5 days of identification, or do not have an established timeframe to report.

- For Centralised Procedure products, EMA requires reporting 2 months in advance. Many NCAs have also adopted this reporting timeframe, as reflected in the graph.

Note: Announced in 2024, the Department of Health in the Philippines is conducting a Drug Shortage Monitoring System Pilot Run where a drug shortage notification would be completed by either 1) Patient/Guardian, 2) Healthcare Practitioner, or 3) Drug Manufacturer/Supplier. The intent of the report is to flag an out-of-stock at a certain time, with the shortage status (e.g., current, anticipated, resolved or discontinued).66

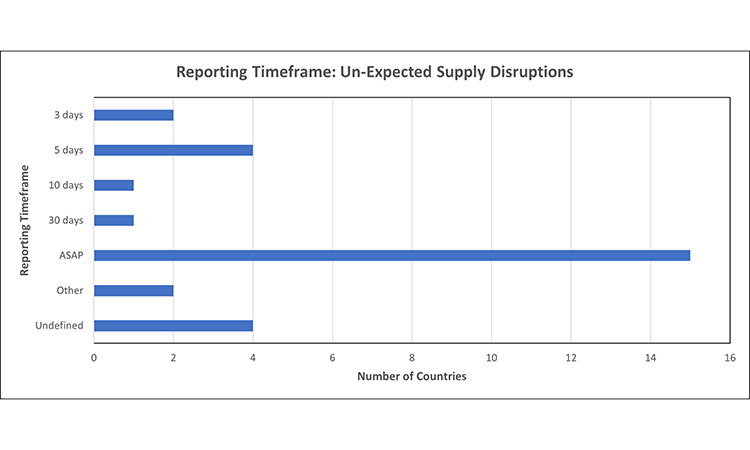

Figure 4: Reporting timeframe trends: un-expected supply disruptions7, 11, 15, 16, 24, 30, 32, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 48, 52, 53, 55, 56, 59, 62, 63, 64, 65

Report un-expected disruptions, once identified

- Other: Depends upon product priority, reason [Australia (Critical Medicine: 2 days | Non-Critical: 10 days); Switzerland (Select significant products: 5 days | Reason for disruption related to quality defect: 15 days | All other products: ASAP)]

- Undefined: No established timeframe for un-expected disruptions

Not all markets have a separate timeframe for reporting unexpected supply disruptions, and these were captured under the ‘undefined’ category. In the markets which have a set timeframe, the window to report once an events been identified ranged from 1-10 days, with the most common being ‘as soon as possible.’

Certain markets had specific timing based on the product’s priority (therapeutic significance). For example, in Australia, critical medicines are to be reported within 2 days, whereas non-critical must be reported within 10 days of identification. In Switzerland, in addition to product priority, the reason for the disruption had a designated reporting window: select significant products must be reported in 5 days, within 15 days if the disruption is related to a quality defect, and all other products are to be reported as soon as possible (ASAP).

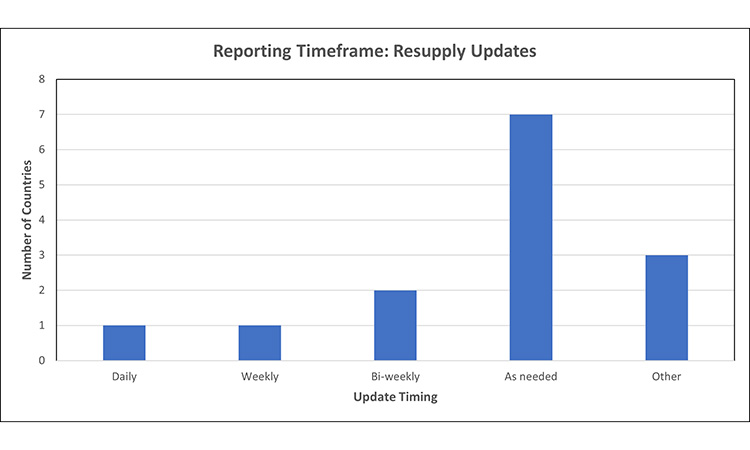

Figure 5: Timing for resupply updates7, 15, 31, 34, 42, 44, 53, 64, 67, 68, 69

- Australia: [Other] timeframe to report updates and resolution is the same as the reporting timeframe (i.e., 2 days for critical, 10 days for noncritical)

- Belgium: As soon as medicine is available, update end date.

- Canada: [other] update shortage report for change or resolution within 2 calendar days from becoming aware or meeting demand if resolved.

- Germany: [other] select finished medicinal products, regular data transmission required. Cycle of every 2 months but can be extended or shortened on case-by-case basis.

Most markets do not have specified frequency for providing resupply updates on previously notified product disruptions, or require updates ‘as needed’, meaning that when a change in resupply timing or relevant update becomes available, the MAH must report.

- Of note, the markets which require daily or weekly updates use a different mechanism to communicate with the HA, such as submission of supply/inventory on a predetermined frequency, as observed in smaller markets such as Canada and Iceland.

- At time of data collection, the FDA required bi-weekly updates sent via e-mail for products listed as in shortage on their public database, regardless of change in status or available information. After data collection, the FDA has changed the mechanism for MAH updates to ensure transparent and accurate information is available to health care providers and the public. Products listed on the FDA DSS drug shortages database are sent to the MAH every 2 weeks, for their review and confirmation that the information posted is accurate.

Theme 4: Permanent Product Discontinuation Reporting Timeframes

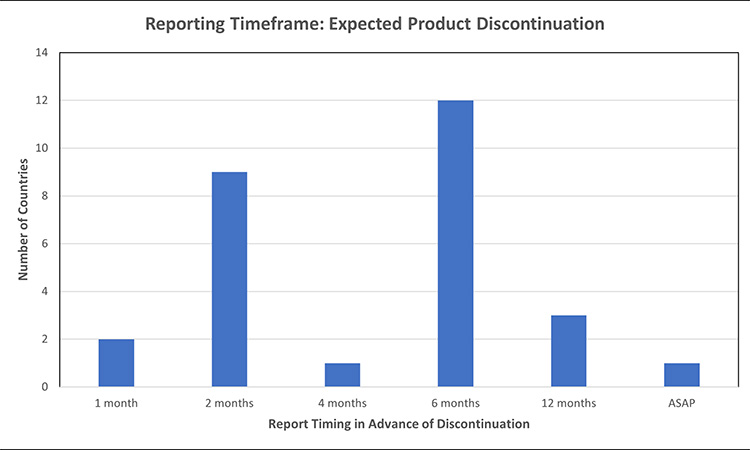

Figure 6: Permanent product discontinuation reporting timelines: expected product discontinuations7, 11, 24, 32, 39, 40, 42, 45, 46, 52, 53, 55, 56, 61, 64, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78

- Australia report discontinuation 6 months in advance for non-critical products, report 12 months in advance for critical products

- Brazil report discontinuation 6 months in advance, or 12 months in advance if leading to drug shortage

- India to report discontinuations for scheduled formulations, and API of such formulations

- Switzerland has different reporting expectations for pediatric medications, which are to be reported 3 months in advance.

When comparing the timeframe to report in advance of an expected product discontinuation of a finished good, markets ranged from 2-12 months, with the most common expectation to report 6 months in advance. Australia had differentiated reporting timeframes based on product priority, 6 months for non-critical products and 12 months for critical products. In Brazil, if the discontinuation is likely to lead to a drug shortage the report should occur 12 months in advance, otherwise report 6 months in advance. While most markets require discontinuation reporting for finished goods, India also requires discontinuation reporting for API of scheduled formulations.

After data collection, the US FDA published guidance which clarified the requirement to report API permanent discontinuations of “covered products” at least 6 months in advance, regardless of the potential to result in a meaningful disruption.79

- The US focuses on a subset of products referred to as “covered products”. Covered drug products are considered those which are life-supporting, life-sustaining, or intended for use in the prevention or treatment of a debilitating disease or condition (including those used in emergency medical care or during surgery) or are critical to the public health during a public health emergency.80

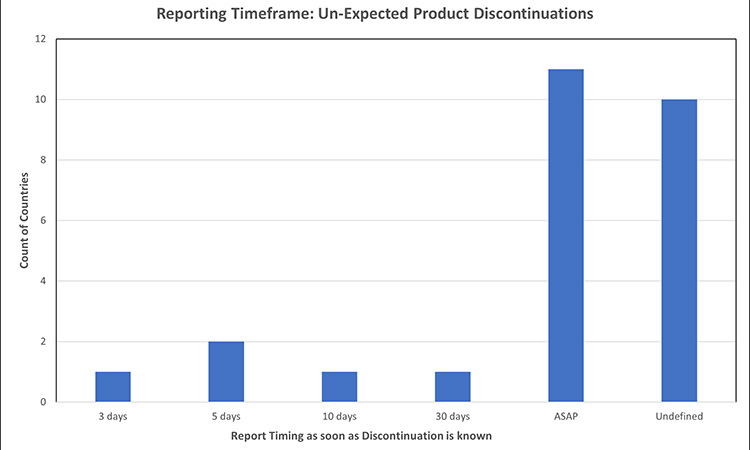

Figure 7: Permanent product discontinuation reporting timelines: un-expected product discontinuations7, 24, 32, 39, 40, 46, 52, 53, 56, 73, 75, 77, 78,81

Most markets do not specify different timeframes for reporting expected vs. unexpected product discontinuations. Where a market recognizes that not all product discontinuances can be expected and has established a timeframe to report, the window ranged from 3-30 days or ASAP, with the latter being the most prevalent. Of the countries evaluated for expected discontinuation timeframes, few had specified timing to report unexpected discontinuations.

Theme 5: Requirements for Risk Management Plans

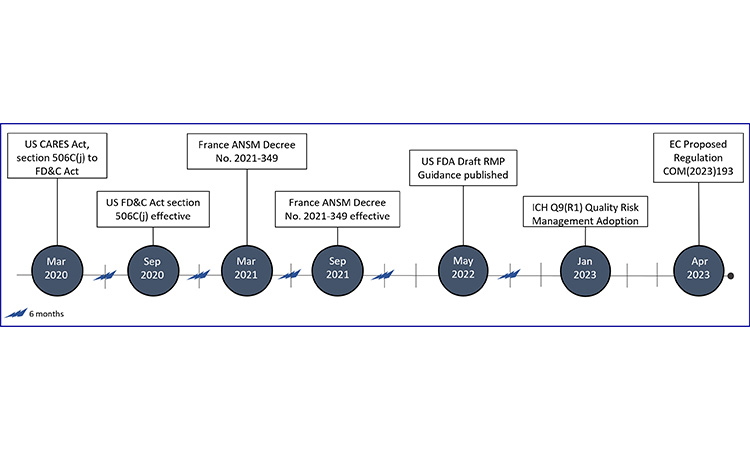

Figure 8: Evolving regulation & guidance for risk management plans

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act); European Commission (EC); Food Drug & Cosmetic Act (FD&C); International Council for Harmonisation (ICH); National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ANSM); Risk Management Plan (RMP)

Due to limited global expectations at the time of data collection, we have created a timeline for the development of RMP expectations across markets.

In France, the obligation for manufacturers to develop shortage management plans (plan de gestion des pénuries (PGPs)) for a subset of products, including evaluation of drug substance, drug products, and critical components, was first published on 30 March 2021, and enforced on 1 September 2021.82 The subset of products or classes of products are referred to as medicinal products of major therapeutic interest (MITMs), where interruption of treatment is likely to be life-threatening in the short or medium term or increase the severity or potential progression of disease.68

In the US, enactment of the CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) in March 2020 added the requirement for manufacturers of a subset of products (“covered products”), including the API of such products, to develop RMPs. Covered products are considered those which are life-supporting, life-sustaining, or intended for use in the prevention or treatment of a debilitating disease or condition (including those used in emergency medical care or during surgery) or are critical to the public health during a public health emergency.83 This requirement became effective on 23 September 2020, and draft guidance for industry was published in May 2022. In the FDA draft guidance, there are different levels of stakeholders defined (i.e., primary, secondary, other). It is important to note that primary and secondary stakeholders are required to prepare RMPs for covered products.84

The revision of ICH Q9(1) guideline “Quality Risk Management” included risk management for product availability, and was adopted by the Regulatory Members of the ICH Assembly on 18 January 2023.85

In April 2023, the European Commission (EC) published a proposal for regulation (COM/2023/193 Final), which outlines the requirements for shortage prevention and shortage mitigation plans. Under this requirement, the Market Authorization Holder (MAH) is to create a shortage prevention and mitigation plan for all medicinal products they place on the market, regardless of therapeutic significance.86

Other European National Competent Authorities (NCAs) which require RMPs to be in place are AEMPS (Spain) and INFARMED (Portugal). In Spain, RMPs are required for products without therapeutic alternatives.87 Portugal requires RMPs for products that have a single facility within their supply chain and have limited or no therapeutic alternatives, or for products which a supply could result in a medium or high health impact. Medium health impact is defined as products with limited or insufficient alternatives, whereas high impact has no therapeutic alternatives.88

At this time, MHRA advises manufacturers to have risk management plans for all authorized products.52

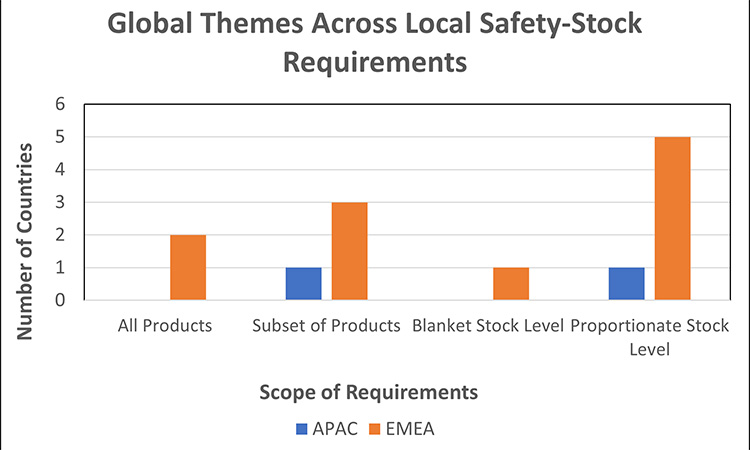

Theme 6: Requirements for Stockpiling/Safety-Stock

Figure 9: Requirements for local stockpiling/ safety-stock68, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98

A sampling of 9 markets were assessed for stockpiling and/or safety-stock requirements:

- 3 markets with laws for the creation and maintenance of a strategic national (state) stockpile to protect national public health in the event of an emergency (e.g., natural disaster, pandemic, etc.). These are managed by government entities.

- 6 markets with local stockpiling/ safety-stock requirements for manufactures to manage and maintain set quantity of product, located in country.

- Some markets extend these requirements to other supply chain actors (e.g., wholesalers, pharmacy's, hospitals, etc.).

We observed similar themes across market requirements for local safety stock:

- Product Scope:

- Majority of markets require safety-stock for products that are critical and/or are vulnerable to shortages across global supply chains (e.g., generic products, hospital products, etc.).

- 2 markets expect all medicinal products meet the required safety-stock level quantity.

Safety Stock Levels:

- Majority of markets have established safety-stock levels to be in proportion with the criticality and/or vulnerability of the product.

- 1 market uses a one-size-fits-all approach (“blanket stock level”) where the quantity of safety stock must sufficiently cover the estimated monthly consumption in market. The product may be removed from the ministry list if not available in sufficient quantity for 60 consecutive days. Note, this does not apply to medicines for rare diseases or innovative treatments.

Some markets have penalties and/or fines for non-compliance with safety-stock requirements, such as loss of designation and reimbursement, delisting, etc.

There are a few markets which use an incentive-based approach where manufacturers are rewarded for maintaining the expected or above expected safety-stock quantities, to ensure supply is available to the local market. Ex.: providing one-off price increases in exchange for maintaining an additional 2 months of safety stock above required quantity, offering price increases to manufacturers of critical medicines with too few existing suppliers, to incentivize market entry and enable sustainable business.

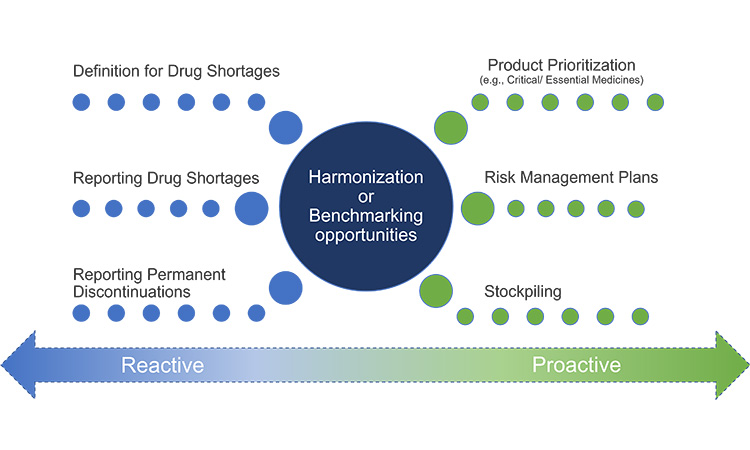

Discussion and Recommendations

Use of proactive measures by a manufacturer, such as effective demand forecasting and application of effective risk management processes, can help prevent or mitigate drug shortages. Reactive measures, such as reporting potential or actual drug shortage events and early engagement with health authorities during unanticipated events, can help minimize or mitigate patient impact.

The current study of the regulatory landscape described in this article and global dialogue indicate that health authorities are increasingly interested in balancing reactive measures with proactive activities. This includes RMPs and digital innovations (i.e., leveraging data analytics for predictive modeling) to improve supply resiliency.4

ISPE agrees with complementary proactive and reactive measures for drug shortage prevention and has emphasized the importance of health authorities engagement and regulatory compliance in the interest of preventing or mitigating drug shortages since the earliest days of the ISPE DSI.5 The recently published ISPE Drug Shortages Prevention Model (DSPM) (see Figure 10) emphasizes that the best balance of proactive and reactive measures will result from layers of preparedness at organizational, operational, and product-specific levels over multiple areas of pharmaceutical manufacturing.6

Figure 10: The ISPE DSPM

Consequently, significant resources and strategy are often required to address the inherent complexity in developing a strong drug shortage prevention program. Continued divergence in health authority regulations or best practice expectations for either proactive or reactive measures has the potential to increase drug shortage prevention complexity and could introduce unintended consequences, such as:

- Stretching limited industry or health authority resources too thinly, resulting in losing focus or capacity to avoid shortages for the most critical therapies for patient outcomes (lifesaving/life-sustaining products)

- Generating supply chain vulnerability and reducing supply chain flexibility through extensive market-specific stockpiling/safety-stock expectations

ISPE Themes for Market-Specific Requirements

From the results of this study of evolving market-specific requirements, ISPE has identified opportunities to converge on the following themes:

Theme 1: Product Prioritization

Critical/ Essential Medicine Definition Themes

Reportable Product Types

Theme 2: Drug Shortage Definitions

Themes in Drug Shortage Requirements (Definition Themes)

Theme 3: Shortage Reporting Timeframes

Expected Supply Disruptions (report timing in advance)

Unexpected Supply Disruptions (how quickly to report)

[Timing for] Resupply Updates (report frequency)

Theme 4: Permanent Product Discontinuation Reporting Timeframes

Expected Product Discontinuations (report timing in advance)

Unexpected Product Discontinuations (how quickly to report)

Theme 5: Requirements for RMPs

Theme 6: Requirements for Stockpiling/ Safety Stock

Theme 1: Prioritization to ensure Product Availability

Critical/Essential medicine definitions

Theme one focuses on critical/essential medicine definitions and reportable product types. Related but inconsistent terms—such as “critical,” “essential,” and “medically significant”—are used across markets to describe products that have high therapeutic importance, such as: critical, essential, medically significant, etc.

The most prevalent expectations for identifying a product with high therapeutic importance is that it either has no or limited alternative therapies or is medically necessary. Generally, products that are lifesaving, life sustaining, or used in emergency situations or surgical settings are considered as essential medicines. Markets that do not have a formal definition for critical/ essential medicines may still have a health authority list of significant products.

The WHO publishes a model list of critical/essential medicines that is updated and published every two years.99 There are a significant number of market-specific critical/essential medicine lists. In 2019, the WHO repository contained 138 national essential medicines lists.100 It is anticipated that this number has only increased. This is because the US FDA Critical Essential Medicines List was established in 2020, and the EMA Union List of Critical Medicines was published in late 2023.101, 102

The following are suggested terms and definitions related to therapeutic importance, given as starting points for global harmonization of critical/essential medicine definitions.

Suggested definitions

Therapeutic significance

Identifies the therapeutic value of a product based on intended use. Generally, products that are lifesaving, life sustaining, or are used in emergency situations or surgical settings that have high therapeutic impact.

High therapeutic significance

Life-supporting, (e.g., oncology), life-sustaining (e.g., anticoagulation, cardiovascular), critical emergency medical care (e.g., reversal agents, normal saline), or curative personalized medicine in a country where the product is registered.

Medium therapeutic significance

Therapies that have significant impact on quality of life (e.g., migraine treatment) in a country where the product is registered.

Low therapeutic significance

Nonessential (e.g., elective therapies) in a country where the product is registered.

Available therapeutic equivalents

The number and volume of available therapeutic equivalents (e.g., generic forms of brand/trade product that are recognized as interchangeable) present in a market can modulate the significance of a product.

Reportable product types

Regardless of the terminology or the existence of a formal definition, where requirements were established for high therapeutic impact medicines, these themes were embedded within a health authority’s drug shortage regulatory framework. The frameworks typically drove the scope for associated requirements, such as reporting disruptions and the need for RMPs or stockpiling and/or safety stock. These markets apply product prioritization for their drug shortage regulatory framework.

Harmonizing the terms and definitions used by various health authorities for critical/essential medicines could significantly help establish more consistent expectations, efficiency, and effectiveness in both proactive and reactive drug shortage prevention measures.

In contrast, a majority of markets require reporting for all products, regardless of therapeutic value or market standing. The following is a snapshot of the global volume of products that may be subject to evolving drug shortage prevention requirements.

Products which may be subject to drug shortage prevention requirements

- In 2017, the WHO’s cumulative list of International Non-Proprietary Names (INNs) contained approximately 9,300 unique, globally recognized, nonproprietary names (generic names). This list increases by some 160 new INNs annually.103

- There are over 20,000 prescription drug products approved by the FDA, and these products may be marketed internationally.104 Of these approved drug applications, some may include multiple products of different strength, concentration, or packaging size.105

- As an estimation of the number of packaging configurations marketed in the US under approved New Drug Applications (including Authorized Generics), Biologics License Applications, and Abbreviated New Drug Applications, the FDA National Drug Code (NDC) Directory contains over 52,000 unique NDCs.106

- There are over 20,000 prescription drug products approved by the FDA, and these products may be marketed internationally.104 Of these approved drug applications, some may include multiple products of different strength, concentration, or packaging size.105

- In the EU, products authorized under National or Centralised Procedure are subject to either local or EMA requirements. Products authorized under National Procedure may be marketed in one or multiple EU countries, subject to unique local requirements within each country.

With the global focus on supply chain resilience, market-specific prevention measures, such as requirements for RMPs, will continue to be established or further expanded. For drug shortage prevention measures to be attainable, product prioritization is required.

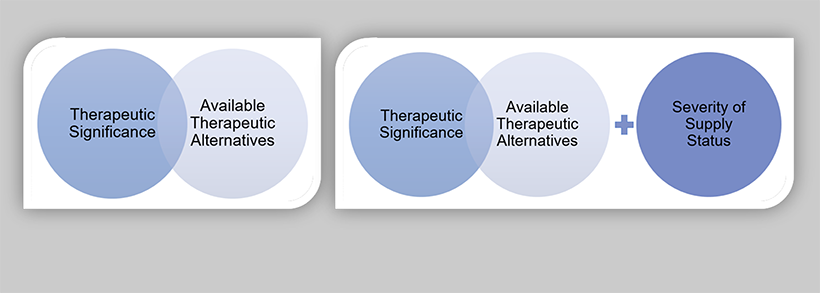

Core considerations to harmonize product prioritization

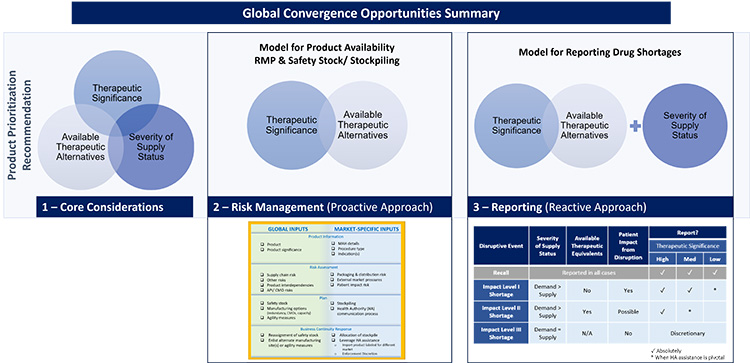

ISPE has identified opportunities to converge on prioritization for product availability concepts in two areas of drug shortage prevention: reactive and proactive measures (see Figure 11). The appropriate level of formality for both reactive and proactive drug shortage prevention measures should be based on the level of risk associated with a loss of patient availability of the products (potential impact of a supply disruption).

Figure 11: Opportunities to converge on prioritization for product availability concepts

The use of the drug product may be the highest prioritization consideration; however, the impact of a supply disruption should not be solely based on the product’s therapeutic significance. This is because not all supply disruptions have equal severity. For example, when an oncology product is unavailable, it is far more significant than when an aesthetic product is unavailable. This is due to the severity and impact on patient outcomes. The overall impact of a disruptive event is connected to the end use of the product, the availability of therapeutic equivalents, and the length of the disruptive event.

For proactive drug shortage prevention measures, therapeutic significance and knowledge of available therapeutic equivalents will help inform the appropriate level of formality for risk management planning. The level of impact for a supply disruption will be informed by severity of supply status, in addition to therapeutic significance and the number and volume of available therapeutic equivalents. Figure 12 illustrates the proposed product prioritization models for drug shortage prevention measures and reporting drug shortages.

Figure 12: Product prioritization models for drug shortage prevention measures (A) and reporting drug shortages (B)

The following core consideration definitions are proposed based on the analysis of the collected data and best practices for supply resiliency.

Core consideration definitions

Therapeutic significance

This identifies the impact to patients and governments’ emergency preparedness measures if a therapy is unavailable. Generally, this includes products that are lifesaving, life sustaining, or used in emergency situations or surgical settings that have high therapeutic impact (e.g., disease progression or death) if supply is disrupted.

The level of impact will drive the appropriate level and formality for risk management planning and will serve as a guide for when manufacturers should include additional information in drug shortage reports to request health authority assistance to mitigate a shortage.

Available therapeutic equivalents

This refers to the fact that the number and volume of available therapeutic equivalents (e.g., generic forms of a brand or trade product thar are recognized as interchangeable) present in a market can modulate the significance of a supply disruption.

For example, if one manufacturer experiences a supply disruption but only holds 1% of the market share, and there is adequate supply of therapeutic equivalents, patients may not experience impact of the disruption. In contrast, if there is a disruption of a high therapeutic impact product without any therapeutic equivalents, even brief disruptions may significantly impact patients’ quality of life and/or health outcomes.

Two key factors of note: First, the identification of suitable alternative therapies (e.g., agents within a same therapeutic class possessing a similar mechanism of action) are not within a manufacturer’s scope to assess, as this would require substitution of therapy. Healthcare providers are accountable for the assessment of appropriate substitute therapy.

Second, at this time, select markets may classify biosimilars as therapeutically equivalent or an alternative therapy. The decision to switch a patient from a biologic to a biosimilar is at the discretion of the healthcare provider, and guidance may be provided to continue with the biosimilar for the course of treatment, even once the disruption has resolved.

Manufacturers may not have full visibility of the available therapeutic equivalents in the market to appropriately evaluate the mitigation of impact. This assessment resides with health authorities, as they are best positioned to evaluate and determine market coverage given their visibility of the market, including potential supply constraints of therapeutic equivalents. Early engagement with health authorities for anticipated or expected disruptions will facilitate this assessment.

Severity of supply status

Pharmaceutical supply is released by manufacturers and subsequently managed by wholesalers and distributers, clinical and hospital centers, and pharmacies. Severity of supply status is related to the amount of product remaining in the entire supply chain and the length of unavailability to the patient.

An example of a less severe supply status is when a manufacturer may have a supply disruption that is resolved before inventories at the wholesalers and distributers, clinical and hospital centers, and pharmacies are detected or depleted. Manufacturers may also be able to manage supply via allocation of stock to minimize the potential for hoarding and enable distribution across regions. In some instances, this can mitigate actual shortages at the retail level.

Product prioritization application case study

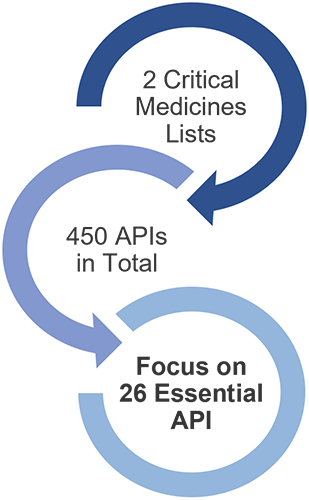

In June 2023, France published their National Essential Drug List.107 In December 2023, the EMA released the Union List of Critical Medicines.102 Between these two separate lists, there is a total of 450 APIs. As part of EU supply resiliency initiatives, a government grant would be provided to enable the relocation of API manufacturing to France and/or Europe.

To ensure resources are allocated to the most critical products, an assessment was conducted in France to re-focus and apply prioritization to identify which products will be relevant. This assessment was performed by public hospital physicians recognized as leaders in their field in collaboration with Ministry of Industry. The prepared lists underwent several peer reviews for concurrence. The result of this cross-stakeholder analysis reduced the list of 450 APIs to focus on 26 essential APIs (see Figure 13).108

Figure 13: France assessment to prioritize essential APIs

This approach aligns with recommendations from the 2016 WHO Department of Essential Medicines and Health Products meeting report, which emphasized that a patient-centered approach to managing shortages is required. “Risk management principles should be used to identify and prioritize measures to ensure the continued supply of medicines that are most needed...”.109 To enable the greatest opportunity for ensuring continuous supply of high therapeutic impact medicines for patients, it is recommended that product prioritization be applied across health authority drug shortage regulatory framework.

Theme 2: Drug Shortage Definitions

Theme two focuses on drug shortage definitions. The definition of a drug shortage varied significantly across markets. The most prevalent consideration was whether there was an anticipated or actual supply interruption, and 56.3% of countries include both anticipated and actual supply interruptions as part of their drug shortage definition.

The second most common was “when supply does not meet demand/patient needs.”110 The WHO conducted a systematic review of shortage definitions, identifying 56 definitions of shortages and stockouts, which varied in terminology, specificity, supply chain perspectives, etc. The nuance across definitions limits the ability to compare and thus may affect the quality of data for forecasting, monitoring, and evaluation.

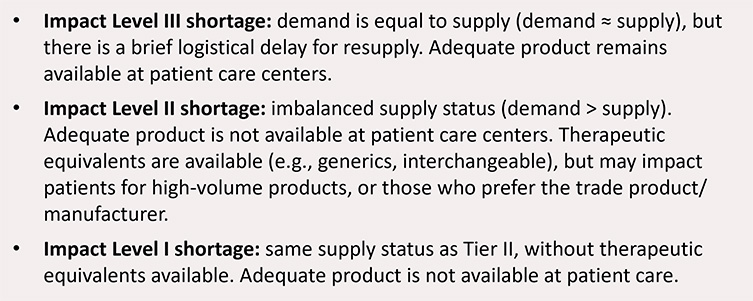

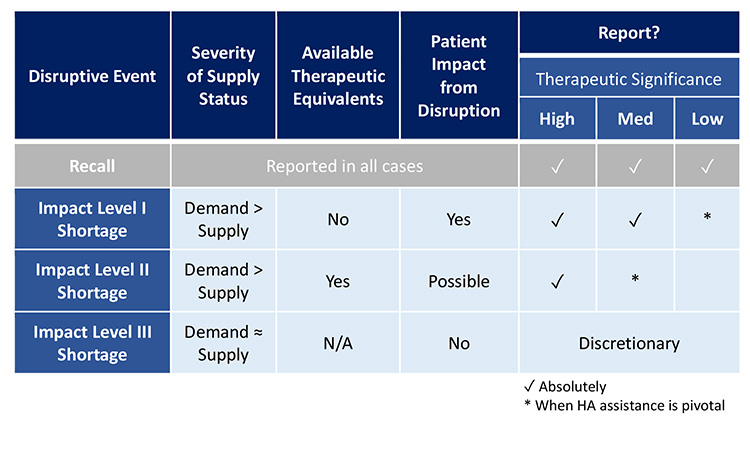

Harmonization of drug shortage definitions would enable consistent reporting expectations, creating efficiencies for both the health authority and manufacturer. Further, alignment would provide meaningful and consistent data for agencies or stakeholders to analyze and increase reliability of predictive modeling for more dependable global demand forecast and supply resiliency vulnerability information. ISPE recommends global adoption of a tiered definition for shortages (see Figure 14).

Figure 14: Impact level definitions for shortages

Theme 3: Shortage Reporting Timeframes and When To Engage HAs

Theme three focuses on a) expected supply disruptions and the reporting time in advance, b) unexpected supply disruptions and how quickly to report on them, and c) timing for resupply updates and report frequency.

Of the markets evaluated, reporting has been established in at least 33 markets and has served since the earliest drug shortage prevention initiatives as an important, reactive approach by health authorities. Reporting opens the door for industry and health authorities to collaborate during challenging circumstances to either prevent the shortage or ensure continued supply.111

Additionally, reporting can provide critical information for product demand forecasting and predictive modeling for the purposes of identifying supply chain vulnerabilities. Accordingly, globally aligned requirements, reporting compliance, transparency, and strategic interaction with health authorities will be pivotal to ensure the best future outcomes for drug shortage mitigation or prevention.

At this time, only 25% of the markets evaluated focus reporting on the most critical situations, 50% of the markets require reporting of shortages for all products, and some markets publish shortage reports for public consumption. ISPE recommends global convergence toward reporting for most critical situations and select public notification and awareness. This is because, as described in the previous discussion regarding prioritization for product availability, not all supply disruptions are equal regarding patient impact.

Increasing global reporting expectations for less significant supply disruptions will ultimately dilute limited resources for health authorities and manufacturers, reducing focus on ensuring continuous supply of therapeutically significant products used by the most vulnerable patient populations. Additionally, some disruptions are so minor that making these events visible to the public without sufficient context may create unintended consequences.

For example, a brief disruption of a nonessential medicine that has therapeutic equivalents available is unlikely to be noticed by patients before the supply disruption is resolved. In this case, if this report is made public, patients may not have the full understanding of what a brief disruption is or entails. Hearing “drug shortage” of one of their medications can cause concern, leading to hoarding and precipitation of a drug shortage of more significance.

Figure 15: Opportunities to Harmonize Reporting Requirements

To assist with consistent and compliant reporting, Figure 15 illustrates how, health authorities could harmonize reporting requirements with respect to the recommended core considerations (therapeutic significance, available therapeutic equivalents, and severity of supply status). To reduce unintended consequences of transparency with public reports, it is recommended that public reporting is limited to only the most significant shortages as identified by the proposed core considerations.

Furthermore, it is recommended that health authorities work with industry to determine what information should be shared with the public and when to best balance transparency and their responsibility to patients while most efficiently resolving the event. Development of transparency of select shortage information between health authorities and industry for the benefit of improving global predictive modeling is also worthy of consideration.

When to report disruptive events can be as impactful as what is reported. In this analysis, reporting timeline requirements across health authorities were varied. For expected supply disruptions, the most common timeframe to report was six months in advance. Because not all supply disruptions can be anticipated, some markets had language within their reporting requirement that provided flexibility to report within the six-month period. For health authorities that established separate timelines for unexpected supply disruptions, the most common timeframe to report was as soon as possible.

To ensure early awareness and transparency, we recommend manufacturers provide an initial notification to health authorities even when mitigations plans are still being evaluated. This opens dialogue between the manufacturer and health authorities to determine the best path forward for minimizing patient impact. Health authorities may also request manufacturers to scale up production to cover a potential market shortfall, and this could be successful with sufficient notice.

Many markets do not have a specified frequency for providing resupply updates following the initial report of a supply disruption. Where language for resupply updates was included in reporting requirements, the most prevalent expectation was to provide as needed. We believe this approach is the most effective and efficient for both health authorities and manufacturers to communicate relevant changes as either resupply has been received and disruption has been resolved, or further delays are expected and may require health authority assistance to reduce impact.

Harmonization on timing to report would be helpful for consistency and development of global best practices; this would in turn be efficient for industry and health authorities. Based on the trends identified, ISPE recommends the following reporting timeframes to report the most impactful shortages, for alignment across markets:

- Expected supply disruptions: Six months in advance, or as soon as practicable

- Unexpected disruptions: ASAP and no later than five business days from identification

- All disruptions: Updates as needed

Theme 4: Permanent Product Discontinuation

Theme four focuses on a) expected product discontinuations and the reporting time in advance and b) unexpected product discontinuations and how quickly to report on them. Product discontinuations are not shortages; however, they can create gaps in the market supply that lead to drug shortages. Accordingly, health authorities have generated requirements around when to report product discontinuations.

For an expected product discontinuation, the most common reporting expectation was notifying the health authority at least six months in advance of the permanent discontinuation date. To accommodate unforeseen or challenging circumstances, language should be considered that provides flexibility to report within the six-month time period for expected permanent discontinuations. ISPE supports this approach because advanced notice provides time for the health authority to evaluate market coverage and work with alternate manufacturers, as needed, to ensure product availability and least impact for patients.

We recommend that market authorization holders (MAHs) consider providing health authorities with notification of significant product discontinuations earlier than the required timeframe based on the previously discussed core considerations (therapeutic significance, available therapeutic equivalents, and severity of supply status) to reduce risk of patient impact to the greatest extent possible. The most common reporting expectations for unexpected product discontinuations was as soon as possible once the discontinuation was identified.

Markets can be dynamic, and forecasts or business events may change significantly; these changes may drive product discontinuations unexpectedly. Additionally, a decision to permanently discontinue marketing may be due to circumstances outside of the control of the MAHs (e.g., supplier files bankruptcy or abruptly decides to discontinue business).

We recommend that manufacturers provide an initial notification to health authorities even when mitigation plans are still being evaluated, as this will ensure early awareness and transparency. It also opens a dialogue between the manufacturer and health authority to determine the best path forward for minimizing patient impact. Based on the trends identified, ISPE recommends the following permanent discontinuation reporting timeframes for alignment across markets:

- Expected permanent discontinuations: Six months in advance, or as soon as practicable

- Unexpected discontinuations: ASAP and no later than five business days from identification

Theme 5: Requirements for RMPs

The application of risk management processes to ensure product availability is the methodology that generates organizational, operational, and product-specific plans to ensure optimal supply and distribution resilience and is achieved during challenging manufacturing or distribution circumstances. Outputs of these processes are RMPs.

RMPs are important for minimizing adverse patient outcomes, reputational damage, and financial disruption for the manufacturer.5 Historically, RMPs (previously called business continuity plans) to ensure product availability have been an internal industry business practice. However, there is now an increasing focus and prioritization of RMPs for the prevention of drug shortages across markets, some of which require plans to be in place for compliance with local health authority regulations.

The revision of ICH Q9(1) guideline “Quality Risk Management” included risk management for product availability and was adopted by the Regulatory Members of the ICH Assembly on 18 January 2023.20 ISPE has a strong focus on drug shortage prevention and published “Risk Management for Avoidance of Drug Shortages,” which describes a general approach for assessing and mitigating the risk of drug shortages through a product’s supply chain and over the life cycle.4. ISPE also recommends ICH Q9 training materials for further guidance and related examples.112, 113

Risk management convergence opportunities for Product Availability

Currently, there are only a few countries with expectations for RMPs. Two markets (France and the US) have established requirements to implement and report out on RMPs to mitigate shortage risks for therapeutically significant products. Two markets (Portugal and Spain) require prevention plans to be in place for products that do not have therapeutic alternatives, and one market (the EU) has proposed prevention and shortage mitigation plan requirements for all marketed products. 114, 115, 116, 117, 118 Because there are few requirements and best practices codified to date, we have an opportunity to reflect on how regulators receive information about the risk management program.

At present, existing requirements make the risk management plan information either reviewable during inspection or require submission periodically. ISPE recommends a global template to guide a meaningful readout of completed RMPs for regulators, which could generate an efficient and consistent approach. Having RMPs reviewable during inspections is preferable because of the resource relief for both regulators and industry. A global template would also serve as a reference for other markets that may be interested in establishing expectations.

The depth and breadth of activity behind any successful RMP may be exhaustive. As discussed previously, this is because risks to supply may occur in any of the ISPE DSPM performance areas for drug shortage excellence. These risks are often outside of manufacturer control, such as climate and geopolitical events.5

Additionally, successful RMP activities may also need to consider business perspectives or market pressures that are beyond the scope of ISPE and not covered in the DSPM. There is a need for aligned communication with health authorities for risk management. Our premise is that industry and regulators alike will benefit from a concise, complete overview of the supply resiliency measures taken for risk avoidance.

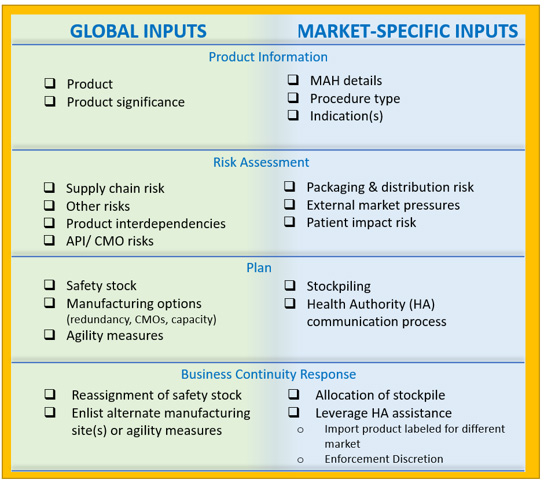

To this end, a proposal for a global regulatory template, “Product Supply Management Plan Template,” is recommended (see Figure 16). The components included in the template are based on a review of current requirements for RMPs and a summation of best practices. They are intended to set the foundation for successful interactions between the MAH and health authorities regarding risk management to ensure product availability.

Figure 16: Key components of the product supply management plan template

A product supply management plan

Biopharmaceutical supply chains often have a global footprint or span several regions, and functional areas of companies may be located in different parts of a country or region or the world. As a result, organizational preparedness and commitment are critical to optimize supply resiliency approaches.5 To assist with proactive alignment, the proposed Product Supply Management Plan template describes global activities and market-specific activities. An alignment framework will also assist when the organization may need to pivot to implement reactive product availability measures during an actual supply disruption event.

Global activities like maintaining a safety stock of materials and components across the supply chain enable agility to address evolving patient needs across markets. Market-specific activities may focus on the manufacturer maintaining a stockpile of finished product labeled for the local market. It is important to highlight that agility measures may be limited by the logistics of mandated stockpiles, such as where they exist and visibility.

The proposed template provides a readout of the organization’s risk management planning to communicate effectively with health authorities. Health authority interactions and potential assistance succeed best with consistent data, support, and messaging from all areas of a company, regardless of function or location.

Communication and risk management

RMPs alignment and communication should also be extended to external partners such as contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs). MAHs should consider when information may need to be provided by or shared with external suppliers. Communication between the primary stakeholder (e.g., MAH) and secondary stakeholders (e.g., CMOs) is essential to understand manufacturing risks for holistic and comprehensive risk management approaches.4

Certain markets have very few suppliers of critical therapies and face resource constraints. For example, some of the most vulnerable active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are for generic sterile-injectable products. Given the extent of products, customers, and product-specific agreements, it is counterproductive to expect CMOs and API suppliers to prepare prescriptive summaries for each customer.

To manage risks to supply of the most critical therapies, CMOs and API suppliers should consider establishing a core set of principles and practices to communicate with customers and their suppliers. They may consider providing detail for specific products and situations, as needed. The following are examples of the type of information they may need to provide to ensure the MAH can successfully complete their work (not all encompassing):

- The output of risk assessment for API significance, supply chain risks, product interdependencies, packaging and distribution risks, external market pressures, other risks, etc. A simple message of assurance, verified by MAH inspection, may be sufficient.

- Risk minimization plans: safety stock, manufacturing options (redundancy, capacity), agility measures, stockpiling, business continuity response, communications plans, etc. A simple message of assurance, verified by MAH inspection, may be sufficient.

To ensure manufacturing risks are understood and effectively communicated by secondary stakeholders to the MAH, the MAH should consider addressing these topics within their quality and/or supply agreement with the CMO. It is important to note that an organization’s risk management planning activity will extend above and beyond what is summarized, and the template does not instruct on every risk management step that may be taken.

Instead, it is intended to prompt the collection and sharing of information that should generally be of most interest to health authorities regarding the actions the manufacturer and CMO are taking to ensure product availability.

With respect to resource investment and execution, ISPE recommends applying the prioritization for product availability measures as described previously (see Figure 12). More specifically, for RMPs that ensure product availability, we propose harmonization toward higher formality RMPs for products with the highest therapeutic significance, that have low to no available therapeutic equivalents, and that may have increased vulnerability for severe supply disruptions (e.g., sterile product with lengthy and/or complex aseptic manufacturing process).

MAHs should also consider developing, maintaining, and implementing plans for products outside of these parameters, as appropriate and with commensurate lower resource investment and/or formality, to ensure reliability of supply for all medicines.

Theme 6: Stockpiling and/or Safety Stock

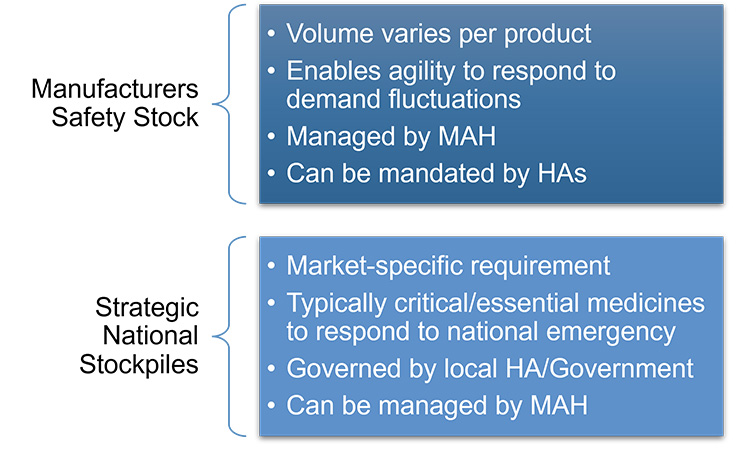

As part of this work, ISPE has recognized an increasing dialogue around the creation and maintenance of national stockpiles and/or mandatory safety-stock requirements. Of the nine markets analyzed for stockpiling and/or safety-stock health authority requirements, there are inconsistent expectations for the types of products and the volume of safety stock required.

There may be different volumes required for each product type and requirement for safety stock in addition to a national stockpile. To differentiate between these two proactive approaches for supply resiliency, Figure 17 describes the general differences between a manufacturer’s safety stock and strategic national stockpiles.

Figure 17: Safety stock versus strategic national stockpiles

Maintaining safety stock and stockpiling by the manufacturer has been a long-standing proactive approach to supply resiliency and can be a valuable element to specific RMPs. However, increasing market-by-market requirements may have unintended consequences because the held product is often not needed and not available to be used elsewhere. Ideally, the product in a stockpile is rotated following “first expired/first out” principles to ensure the product within shelf-life requirements of the user is supplied.119, 120, 121

Rotating the stockpiled material generates complexity and taps into limited resources. Therefore, increasing stockpiling and /or safety-stock requirements will likely increase resource investments, and stretch supply of materials, components, drug substance, and finished drug product for many global companies. This inadvertently generates supply disruptions from the strain or motivates unhelpful business practices. For example, requirements have been enacted that mandate a manufacturer to hold at least two months of stockpile intended for the market with fines as a consequence for noncompliance.122

To maintain compliance and avoid fines, a manufacturer may hold on to the stockpile and withhold distribution to the market even during a shortage event, unless health authority approval is granted. This framework reduces supply agility and response time to address patient needs and adds administrative burden to both the health authority and manufacturer.

The key to supporting uninterrupted supply of a portfolio of products is to emphasize all areas of the DSPM, including but not limited to the application of forecasting, appropriate multiple sourcing or agility measures, safety-stock practices, and stockpiling, with sustained manufacturing performance to drug shortage prevention.5 An approach where safety stock is controlled by the manufacturer will enable the most opportunities for supply agility to address unmet patient needs.

Exhaustive strategic national stockpiling or mandatory blanket safety stocks across all products may be counterproductive because they can tie up resources at the operational level, hold inventory that could be distributed to alleviate downstream constraints elsewhere, and waste resources that are in direct conflict with sustainability goals. There would be greater benefit in evaluating situations on a case-by-case basis to ensure patient needs are met versus creating additional requirements that add barriers to supply resilience.

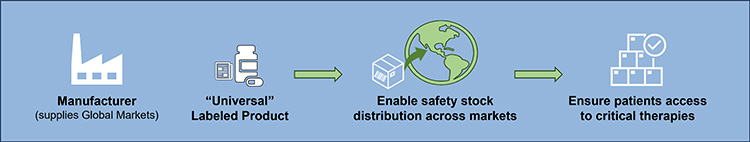

An alternate approach that may serve individual country needs better is global convergence toward an international stockpile that would allow a product with a universal label to be distributed across markets. It provides a holistic approach to stockpiling that would enable movement of prioritized product safety stock to markets in need for increased supply agility (see Figure 18). This approach is based on regulatory pathways some markets use today to grant regulatory discretion to enable importing of product labeled for another market.

Currently, there is no mechanism to do this on a global scale. Enabling this opportunity would require global harmonization and likely legislation changes. Creation of a global regulatory pathway for an international stockpile could create efficiencies for both individual and other health authorities, as well as help companies balance the growing safety stock and stockpiling requirements across the globe.

Beginning with opportunities to create a regional stockpile may be more feasible in the near term, which will serve individual country needs and facilitate progress toward achieving an international stockpile. Because legislation change and global harmonization can take time, health authorities could create interim regulatory practices for acceptance of a universally labeled product to enter the market. Leveraging digital solutions such as blockchain could also enable an agile, global supply chain.

Figure 18: Holistic approach to stockpiling

Conclusion

Given the importance of ensuring continuous supply of biopharmaceutical products for patients, the increasing pressures on supply chains, and the rapidly evolving regulatory drug shortage landscape, we anticipate diversity in health authority expectations intended to ensure or bolster product availability could continue to grow. From our study we have concluded that:

- Convergence opportunities exist

- Prioritization is key to success

- Product availability RMP practices are in a transformational period

- Optimum stockpiling and/or safety-stock requirements should be streamlined and flexible

Suggestions presented throughout this article are intended to serve as a starting point to begin an open dialogue with industry and regulators on potential regulatory harmonization opportunities for requirements or expectations related to drug shortage prevention. The key elements of the convergence opportunities we have observed are summarized in Figure 19. Harmonizing definitions and approaches will create efficiencies for health authorities and industry to focus on the most significant issues, reducing timelines of disruptive events and patient impact. These efforts will ensure patients remain top priority.

It is important to acknowledge that there are many factors beyond the topics discussed in this article that can contribute to drug shortage events or restrict supply resiliency, e.g., government structures, geopolitical events, economics, and healthcare systems. These other important topics are excluded from this work because they are beyond the scope of the ISPE DSI. The ISPE DSI team focuses on the technical, scientific, manufacturing, quality, and compliance aspects of a company’s supply chain, and the issues related to its ability to source, manufacture, and distribute products.

Any effort to effectively address the complex and multifaceted issues contributing to drug shortages requires close technical collaboration and clear communication between the pharmaceutical industry and global health authorities. ISPE has had a long-standing commitment to facilitating communication and progress between the different sectors of the pharmaceutical industry and global health authorities related to drug shortages.3 ISPE and the DSI team of industry experts continue to be prepared to provide platforms for discussion with appropriate government or regulatory agencies in support of global harmonization activities.123

Figure 19: Global convergence opportunities summary

Acknowledgements

The ISPE Global Convergence Opportunities Team, with members from the ISPE Regulatory Quality Harmonization Committee (RQHC) and the ISPE Drug Shortages Initiative (DSI) Team, partnered to collectively develop the content for this article and special recognition is extended to the following members:

ISPE Global Convergence Opportunities for Drug Shortage Prevention Authoring Team

Jessica L. Hale, PharmD, MSD

Diane L. Hustead, MSD

Gregory Rullo, Astra Zeneca

Lynne Ensor, PhD, NSF

Flavia C. Firmino, Pfizer

Jean-Francois Duliere, ISPE

Connie Langer, Pfizer

Serina Lin, ISPE Emerging Leader

Patriz Miga Placer Lintag-Raymundo, Pfizer

Demetra Macheras, AbbVie

Isabel García Mora, Lonza AG

Xin Yi Ong, PhD, Pm Project Services Ltd

Georgina Pearson, ISPE Emerging Leader

Christopher Potter, PhD, ISPE

Daniel Thio, ISPE Emerging Leader

Thomas Zimmer, ISPE

ISPE Advisors, Reviewers, and Contributors

Maria Amaya, Genentech, A Member of the Roche Group

Marta Antunes, MSD

Janelle Derbis, PharmD, MSD

Ylva Ek, Robur Life Science Advisory AB

Stephen P. Errico, PE, Biogen Inc.

Celeste Frankenfeld Lamm, Ph.D., MSD

Gonzalo Gómez, Roche International Ltd.

Shanshan Liu, No Deviation Pte Ltd.

Christine M.V. Moore, PhD, Organon LLC

Sujatha Narayan, Genentech Inc.

Tommy Pourmahram, McKesson

Vivien E. Santillan, Novatek International

Sandra Wainwright, PhD, MSD

Jennifer Wilhelm, MSc, MBA, RAC, MSD

Carol Winfield, ISPE