Quality Considerations in Disaster Recovery: A Case Study

Due to the growing digitalization of the industry, we are highly dependent on information technology (IT) systems and data. The basic ability to execute our pharmaceutical business and decision-making processes relies on the permanent availability of these IT systems and data to ensure compliance and efficiency of our business operations. But numerous factors—including criminal activities, political unrest, and environmental hazards—have made disaster recovery (DR) and business continuity planning essential.

A Growing Need for Disaster Recovery Plans

Cybersecurity attacks have been on the rise for many years, with ransomware and phishing being the top threats to our industry. A 2023 survey found that 66% of organizations experienced at least one ransomware attack.1 How can the life sciences industry become more resilient against those attacks while acknowledging that 100% security cannot be established?

Appendix O10, “Business Continuity Management,” and Appendix O11, “Security Management,” in the ISPE GAMP® 5 Guide: A Risk-Based Approach to Compliant GxP Computerized Systems (Second Edition) provide excellent guidance for requirements and measures to prevent security incidents from happening and keep the business operational during a disaster.2 Most companies rely on their backup and restore capabilities for their DR strategy; therefore, the backup setup, verification, and monitoring described in Appendix O9, “Backup and Restore,” should be considered.2

Other standards also provide detailed guidance:

- ISO/IEC Standard 27000:2018 provides an overview of information security management systems,3 including ISO 27031, A Standard for IT Disaster Recovery.

- ISO/IEC Standard 22301:2012 sets out the requirements for a business continuity management system.4

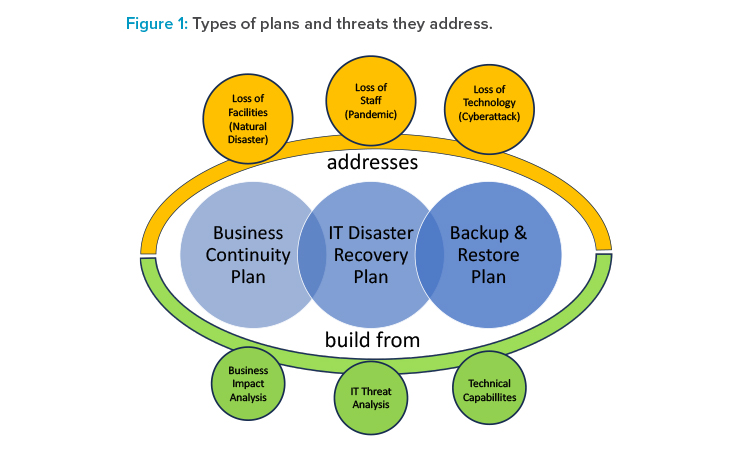

DR, business continuity, and backup and restore are closely connected and need to be managed throughout the entire system and data life cycle (see Figure 1).

DR aims to anticipate and assess the impact of disasters and to build strategies and plans for how to recover from such disasters. In this context, a disaster may be related to IT (e.g., cybersecurity incident), staffing (e.g., pandemics), or facilities (e.g., natural disasters). Business continuity addresses how to keep the business processes operational in case of any disaster. In case of an IT-related (including IT facilities) disaster, the backup and restore capabilities are typically key to restoring IT systems, data, and services.

However, cybercriminals are increasingly designing their ransomware code as a time bomb to hinder the company from easily restoring their IT systems and data. Rather than encrypting data immediately after it gets past the corporate firewall, it begins to infect the data over time. Days, weeks, or months later, when the infected data has been backed up, it initiates the encryption of the corporate data. As the backup is also infected, it cannot be restored easily and may encrypt already restored data or systems.

The Human Factor

Humans tend to believe that disasters “only happen to other people.” And even if a disaster did happen to them, they are convinced that they would know how to deal with it. This combination of over-optimism, normalcy bias, and tendency to overvalue known short-term costs and under-value unknown long-term rewards is referred to as the “preparedness paradox” and is reflected in sentences like:

- “ Why would anyone attack us? We are too small/insignificant/etc.!”

- “ We have state-of-the-art IT protection. We are safe.”

- “ If the data center blows up, I’ll just walk over to the next IT store, buy new equipment, and bring it all back in no time.”

- “ If an IT system goes down, we can always restore it from the backup in no time at all. No further planning is required.”

- “ What do you mean when you say, ‘We need to test if we can restore data/systems from the backup?’ We are using a market-leading software, and it has not given us any errors or alarms. It works!”

- “ If the IT goes down, we just go back to paper. It worked in the past, didn’t it?”

This human trait often leads to:

- Lack of time, resources, and willingness to take this seriously and contribute (e.g., “This will never happen, so this is a waste of time.”)

- DR or business continuity plans (BCPs) that are not fit for purpose (e.g., badly designed or not up to date)

- Lack of robust testing of the plans (e.g., scenarios are too simple, assumptions are too positive, everything is simulated and not tested, or tests are always postponed due to “more urgent business”)

- Missing concepts for processing paper records and reintegration of these records into the restored computer systems

This is also reflected in the fact that only 50% of all companies test their DR annually or less frequently, whereas 7% do not test their DR at all.5 But when a major security incident leads to widespread system issues and data loss strikes, what are the best practices? What are the benefits of appropriate planning? And what are potential challenges from a quality perspective?

In this article, the authors have created, based on several DR scenarios they have been involved in, a hypothetical case study of a successful ransomware attack to highlight potential pitfalls and provide guidance on how to restore regular business and compliance. However, the guidance can easily be adapted to other incidents that lead to significant data loss or system unavailability.

The Importance of Plans

Every regulated organization should have adequate DR and BCPs. These plans should cover a variety of potential disasters and provide detailed guidance on how to operate during a disaster and recover back to normal processes as quickly as possible. Furthermore, required roles and responsibilities should be defined and individuals to fill those roles identified.

Organizations that do not spend the necessary time and resources on creating and maintaining these plans on an ongoing basis have already fallen for the first pitfall in DR. Without such plans, the significant amount of confusion that invariably happens once a disaster strikes is prolonged unnecessarily.

The organization may be paralyzed at the IT level and communicate through unusual channels, e.g., via social networks. But well-designed plans and robust communication can reduce the duration and intensity of this period significantly. Without a plan, communication channels and roles and responsibilities are unclear. Most organizations may not know what to do, how to communicate, or how to get further information.

DR and BCPs are worthless if they cannot be accessed in a disaster. Separate, secure, and accessible storage should be established for these documents, and supporting documentation (e.g., the business impact analysis or the risk assessment) should also be stored in that location. The value of DR and BCPs can also be diminished if they are not frequently reviewed and adequately tested to ensure they are fit for purpose.

The level of preparedness for such disasters can be assessed through internal audits that focus on DR and/or ransomware readiness. The Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) provides focused audit programs like the “IT Business Continuity/Disaster Recovery Audit Program” for these areas.6 These audits may verify that the design of the IT landscape is resilient to widespread ransomware attacks, e.g., via an appropriate network architecture, as well as the existence and quality of plans and procedures.

A Hypothetical Case Study: Setting the Scene

Disasters can strike your organization in many ways, and every disaster is unique and requires unique recovery activities. Common to all IT disasters is that data and systems are either lost, not available, or stolen. This article does not consider natural disasters and similar incidents where the health and safety of the organization’s staff are directly at risk. The case study that we want to use as an example throughout the article is a midsized pharmaceutical company that has been hit by a ransomware attack.

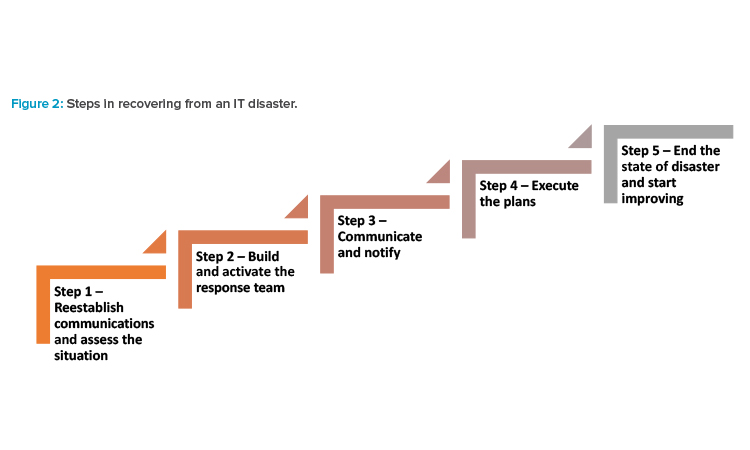

The ransomware encrypted most of the connected endpoint devices, infected system backups over a period of three months, and encrypted most servers in the organization. Also, data that was stored on cloud infrastructure had been encrypted. Electronic communication via email or collaboration platforms was not possible. The company has BCPs and an IT DR plan that is available on every site as a paper printout. A permanent disaster hotline is available for all staff. In our hypothetical case study, the organization followed the following DR steps (see Figure 2).

Step 1: Reestablish Communications and Assess the Situation

As a very first step, the organization needs to evaluate the extent and impact of the IT disaster. To enable any kind of DR activities, staff must identify the affected systems, data, and infrastructure. To achieve this, it is critical that key decision-makers, as outlined in the relevant plans, are informed of a potential disaster as quickly as possible and have the means to establish communications quickly and permanently without having to rely on company resources that may be unavailable in a disaster.

It is critical that the IT, quality, and relevant business, legal, and human resources departments are included in these early communications and assessments, as not only the impact on technology must be determined but also the potential downstream impacts on regulatory compliance, product quality, data integrity, patient safety and privacy, financial stability, and company reputation.

Once the damage has been contained by isolating affected systems to prevent further damage and after the extent of the disaster has been roughly established, the “responsible person” needs to declare the disaster. This may be the CEO, or other leadership, but it should be as outlined in the applicable plan, with backup leaders as needed should someone be unavailable.

Declaring the disaster is important because the company may suspend and/or adapt processes for the duration of the disaster, e.g., falling back on paper documentation and processes for impacted IT or business processes. The initial investigation must identify the technical root causes of the disaster so that any vulnerabilities or weaknesses that contributed to it can be considered when planning and making decisions on what to do next.

The leadership of the organization now needs to determine and balance the following aspects:

- How to enable business and reduce or limit financial loss for the organization (e.g., through short-term workarounds)

- How to restore manufacturing to produce critical products to ensure patient safety

- How to manage potential technology and IT supply chain constraints

- If and how the disaster impacts regulatory compliance

- How to handle data privacy implications (e.g., for data theft)

- How to meet legal/regulatory obligations (e.g., shareholder notification)

In our hypothetical case, communication could quickly be reestablished because the board of directors kept a list of the up-to-date contact information of the key decision-makers and other critical staff in a safe, “break-glass” location. That allowed key communications to be restored via social media, and meetings could be organized and conducted.

The initial assessment showed that affected systems included:

- Manufacturing systems, including the manufacturing execution system (MES)

- Laboratory systems, including the laboratory information management system (LIMS)

- Document management systems, including all standard operating procedures (SOPs)

- Pharmacovigilance system

- Email and collaboration platforms, intranet, and extranet

- IT systems for backup, including the configuration management database (CMDB) and service desk

- Financial systems

The root cause was a ransomware attack that was introduced to the organization by unknown means. Further forensics are initiated to identify the root cause. After careful consideration, it was decided not to pay the ransom and use the services of a prequalified IT security service provider to analyze the attack, determine the exact circumstances that introduced the ransomware to the organization, and help recover the data and systems.

Step 2: Build and Activate the Response Team

As a next step, the organization needs to assemble a team of experts responsible for managing the recovery process and assign roles and responsibilities to team members. With the team, the organization needs to prioritize the systems and data recovery in more detail and identify potential obstacles.

In our hypothetical case, the company made the following high-level decisions for response teams. Dependencies between the workstreams were identified and tasks were worked on in parallel wherever possible. The response team leaders aligned themselves in daily meetings.

Response team: infrastructure

- Priority 1: Establish a secure infrastructure environment, including backup services.

- Priority 2: Reestablish email and collaboration platforms, intranet, and extranet.

- Priority 3: Reestablish the CMDB and service desk.

Response team: applications and systems

- Priority 1: Reestablish the MES.

- Priority 2: Reestablish the LIMS.

- Priority 3: Reestablish the pharmacovigilance system.

- Priority 4: Reestablish the financial systems.

- Priority 5: Reestablish the document management systems, including all SOPs.

Response team: quality

- Priority 1: Assess risk to data integrity, product quality, patient safety, and regulatory compliance.

- Priority 2: Document the disaster, including all decisions and actions.

- Priority 3: Stand up support teams that establish basic processes for recovery activities.

Response team: legal

- Priority 1: Assess legal obligations and restrictions, including data privacy, financial, and other regulations.

Step 3: Communicate and Notify

It is crucial to inform relevant staff of the disaster and the next steps to be taken to reestablish normal operations as soon as possible as well as provide potential instructions for end users. This can, for example, be communicated via established support channels, if still available, or via announcements over a disaster hotline that has been established before the disaster.

Furthermore, the established group of decision-makers must decide on the potential need to communicate the disaster externally (e.g., to regulatory authorities, partners, or customers). All external communication, including to the media, must be tightly controlled and managed (e.g., for shareholder information).

In our hypothetical case, a toll-free disaster hotline number was available and was used to relay information and general instructions to the organization. Through this line of communication, which was supported by social media, town hall meetings could be organized to provide further information to the employees.

Regulatory authorities should be informed that the company will be unable to produce essential products that some patient groups depend on. The board of directors should inform all impacted partners. Communication with the public, including customers, is initiated, and overseen by the board of directors and managed/executed by the public relations department.

Step 4: Execute the Plans

By their very nature, BCPs and IT DR plans must be very flexible because disasters can strike an organization in many ways and can take many different forms. At the same time, the plans need to outline technical dependencies clearly and be based on the business impact analysis and the risk assessment that was done when the plans were created. With support from subject matter experts, the response teams now need to decide which parts of the plans must be implemented and build a strategy for recovering services and systems.

This is not the time for parts of the organization that did not contribute to plan development to question the plan’s basic structure. Any changes to the established plans, e.g., reprioritization of recovery activities, may require an impact and risk assessment to avoid undesired effects on the overall recovery activities and should require approval by the organization’s senior management.

The appropriate quality functions should be involved throughout the entire execution of BCPs and IT DR plans. Even in case of a disaster, quality and regulatory compliance must not be neglected. In such situations, quality functions need to be “enablers” that help establish critical documentation and records during recovery activities. The documentation will not be perfect but should be sufficient to allow justified decision-making on the release of systems and data that could impact product quality, patient safety, or data integrity.

Considering the challenges the organization is facing in such times, flexibility and critical thinking by everyone is absolutely required. In our hypothetical case, the analysis of the attack showed that:

- The attack already happened months ago and infiltrated all backups.

- The attack vector was phishing.

- The preventive technical controls were ineffective and not well maintained.

- The historically grown infrastructure was not designed to contain such an attack to a section of the IT landscape.

- The IT security service provider can decrypt the affected files with special tools and software re-engineering.

The BCP and IT DR plan provided the required order for the recovery of systems and data. The quality organization faced the following challenges that had not been considered in the plans:

Our company produces important (potentially life-saving) products that some patient groups depend on. What is the best way to avoid drug shortages without sacrificing product quality?

1: Drug shortages

“Our company produces important (potentially life-saving) products that some patient groups depend on. What is the best way to avoid drug shortages without sacrificing product quality?”

The BCP for the manufacturing process outlines and documents alternative ways to operate in case IT systems are unavailable. The approach was evaluated (including a risk assessment by quality assurance), adapted based on the nature of the disaster and the recovery planning, and discussed with applicable regulatory authorities as outlined in the European Medicines Agency’s regulatory guidance on drug shortages.7 Once implemented, additional reviews, verifications, and checks are performed and documented to ensure data integrity, patient safety, and product quality are not at risk.

2: Documentation for audits and inspections

“How do we document the incident, the root cause, and the sequence of the events in such a way that it can be presented and defended in audits and inspections?”

Processes that are especially timebound like pharmacovigilance can be a significant challenge because regulatory timelines must be met during the disaster.

It was decided that a dedicated resource in quality would maintain a chronological issue log containing all activities and decisions. All quality and IT staff (including the IT security service provider) must copy this resource on all relevant communications. All created documentation must consider potential needs for confidentiality.

3: Interim processes

“How do we provide the organization with interim processes until the SOPs from the document management system have been restored?”

Interim processes and supporting templates are created by the quality organization and provided via a cloud storage provider. These processes are abbreviated, focusing on the essentials, and not extensively reviewed but approved by senior quality executives. The following order has been established for the creation of quality processes:

- Infrastructure qualification

- IT change control

- Validation of computerized systems

Training is done virtually, and attendance is recorded manually. In parallel, non-IT-related processes must be reestablished or restored (e.g., for manufacturing and quality control of medical products). The prioritization should be based on patient safety, product quality, and data integrity.

4: Data integrity

“How do we maintain data integrity during and after the disaster?”

Because alternate ways to operate involved the creation and/or processing of paper documentation, a task force was created to ensure appropriate handling of the paper records throughout the entire data life cycle and to develop a strategy to integrate the data once the IT system is available again.

This approach, already documented in the BCP and the business process requirements, was adapted for every system and business process individually, based on the specifics of the disaster (e.g., anticipated time to full system recovery).

Processes that are especially timebound like pharmacovigilance can be a significant challenge because regulatory timelines must be met during the disaster. After the disaster, all data must be integrated into the restored system to allow the processing of follow-up information and the ongoing analysis and evaluation of product safety.

5: Qualification of IT infrastructure

“How do we record the qualification of the IT infrastructure, including potential changes to the architecture and design to prevent such incidents going forward?”

The recovery activities start immediately based on security recommendations by the IT security service provider and are recorded informally, covering:

- Date and time of the activity

- Specification and configuration of the infrastructure

- Required verification activities

- Name of the person performing the activity

The quality department will establish an abbreviated process and templates for infrastructure qualification to be used going forward. When published, the process will be executed retrospectively and based on risk for already established infrastructure at that point in time. All created records must consider potential needs for confidentiality. The usage of tools and automation, where possible, is highly recommended.

6: Decryption tools

“How do we qualify the tools used to decrypt the data and systems? How do we know the data is correct and complete and the systems are fit for the intended use (also considering the changes to the underlying infrastructure)?”

Existing tools of the prequalified IT security service provider are used as is and qualified retrospectively. The qualification will leverage the existing vendor documentation and technical integrity checks to the extent possible. The testing of the tools focuses on:

- Identifying unencrypted files, databases, and servers

- Encrypting these items with the original ransomware in a controlled environment

- Decrypting them with the existing tools of the IT security service provider

- Verifying that the items and data are the same after processing and free from malware

If possible, the qualification of the recovery tools will be completed before the recovered systems and data are used in production again. All created documentation must consider potential needs for confidentiality and IT security. Systems that do not function as intended due to tighter security will be prioritized and investigated. All decrypted systems that are used productively without the qualification of the tools completed will be reviewed and released by the process owner and senior quality management.

7: Ransom situations

“How do we deal with data loss, e.g., data or systems that cannot be restored?”

For every logical group of lost data, a corrective and preventive action will be issued to investigate how the data was lost, the risk or impact of this data being lost, and measures that can be taken to prevent reoccurrence. Examples of data loss risks and impact include regulatory noncompliance (e.g., retention period), inability to recall the product, incomplete drug safety data, and lost business and financial impacts. Again, all created documentation must consider potential needs for confidentiality and IT security.

A similar approach could (and should) be used in scenarios where the ransom is paid and the key for decryption is provided.

To pay or not to pay

On average, 46% of the companies that were hit by a ransomware attack in 2022 paid the ransom, which was, on average, around $1.5 million US.1 That makes ransomware a lucrative business model for cybercriminals, but law enforcement agencies recommend not paying the ransom. In fact, paying the ransom could even be illegal, because it could be violating the US Office of Foreign Assets Control’s regulations or other similar regulations9 or interpreted as funding terrorism under the United Kingdom’s Terrorism Act.10

Still, in many cases, it is easier, faster, and cheaper to pay the ransom than to recover from backup. The basic assumption is that if organizations pay the ransom, the attackers will provide a decryption tool and withdraw the threat to publish any potentially stolen data. However, payment does not guarantee all data will be restored. In reality, on average, only 65% of the data is recovered, and only 8% of organizations manage to recover all data.8 After all, cybercriminals are not necessarily IT experts or software developers that you can trust.

In fact, encrypted files are often unrecoverable because the attacker-provided decryptors may crash or fail. In such cases, you may need to build a new decryption tool by extracting keys from the tool the attacker provides. This raises significant quality and data integrity concerns, as already outlined previously in step 3. Finally, “there is no honor among thieves”—paying a ransom may increase the likelihood of repeat attacks on an organization. The cybercriminals now know that your system is a good target and that you will pay a ransom.

Step 5: End the State of Disaster and Start Improving

When a predefined recovery level has been reached (e.g., all critical systems recovered), the state of disaster should be formally ended. This can be done for entire organizations or for individual areas of the business (e.g., when systems and/or data have been restored) so that the associated processes can be executed as they were before the disaster.

At that time, a thorough analysis of the incident should be performed to identify further areas of improvement. By this time, your organization will have a good estimate of the losses the company has suffered due to the incident. Based on the analysis, losses, and risk assessment, an improvement plan should be developed that may include:

- A review of processes to create and update BCPs and IT DR plans

- Technical and design controls to increase security, such as:

- Hardening of infrastructure

- Zoning of networks

- Creating a DR instance of critical systems

- Organizational and procedural controls, such as:

- Storing of BCPs and IT DR plans outside of the company network

- Emergency contact information

The plan’s outcome and analysis should be considered in the remaining recovery activities and the implementation of all new systems and infrastructure going forward.

Best- And Worst-Case Disaster Recovery Approaches

What if a company is not as well prepared as the one in our hypothetical case study? Table 1 contains best-case approaches as outlined in the case study and worst-case alternatives and their consequences. This list is not exhaustive and is meant to encourage critical thinking and discussion around DR and business continuity.

Conclusion

As Scottish poet Robert Burns said: “The best-laid schemes of mice and men go oft awry.” However, if plans are created with the necessary care, they can be invaluable in an IT disaster. They reduce the initial state of confusion and allow for the prioritization of activities based on already performed risk assessments. Preselected and prequalified service providers for forensic analysis and data restoration may further reduce downtimes and speed up recovery activities.

The challenges to the quality organization during DR are many. Often activities are done in parallel, processes may be unavailable or not fit for purpose, and documentation may not be as controlled as it was when all systems were available. A pragmatic approach that focuses on product quality, patient safety, and data integrity and that is based on risk and critical thinking is essential.

Depending on the nature of the disaster, the quality organization may need to:

- Support the teams in the creation of required processes to support recovery activities.

- Support infrastructure qualification and computer system validation activities for systems that are restored or rebuilt.

- Assess data integrity of restored systems and data, including data integration activities after the system is restored.

- Support risk-management activities to ensure the effectiveness of workarounds and other short-term measures.

- Document the disaster, the subsequent analysis, the root cause, the corrective actions, and the lessons learned.

| Item | Best-Case Approach | Worst-Case Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Availability of DR plan and BCPs | The company has BCPs and an IT DR plan that are available on every site as a paper printout. | The company’s BCPs and IT DR plans are encrypted and unavailable. It takes several days to piece these together based on outdated drafts, meeting notes, and other materials that were not encrypted. |

| Initial Communications | Communication can quickly be reestablished through contact information in a “break-glass” location. This allows key communications to be restored via social media, and meetings can be organized and conducted. | The contact information is distributed (e.g., on individual cell phones) or unavailable. It takes weeks to contact all the key decision-makers and contributors. Meetings with all relevant contributors are difficult to organize. Decisions taken without all contributors’ input may be revised later, adding to the already existing confusion. |

| Further Communications | The already established toll-free number allows sending information and instructions to the employees. A town hall meeting was organized to explain the situation and to explain the next steps. The controlled external communication meets legal requirements (e.g., for shareholder information) and limits the damage to the company’s reputation. | Information and instructions cannot be relayed to the employees, resulting in anxiety and panic. External communication is not tightly controlled, leading to legal issues with shareholders and authorities, excessive damage to the company’s reputation, and loss of potential business. |

| Initial Assessment | Communication was reestablished quickly, and an initial assessment and high-level root cause analysis was completed. The extent of the disaster was quickly established, and the necessary actions and steps were planned and initiated. | Due to lack of communication, it takes several days to establish an initial assessment and high-level root cause analysis. Actions and next steps are planned based on available information, but actions and priorities change as more information becomes available over time. |

| Prequalified IT Security Service Provider | A specialized, qualified, and trustworthy IT security service provider can be brought in quickly to support DR with technical expertise, forensic services, and consultancy. | An IT security service provider is identified based on an ad hoc web search. The negotiations and contractual agreements are accelerated but still take several days. Later, it is observed that the provider was unfamiliar with GxP environments and too expensive. |

| Prioritization | The BCPs and IT DR plans provide the required order for the recovery of systems and data based on predetermined technical dependencies and risk assessments. | After the BCP and IT DR plan have been recovered, the prioritization is questioned, as technical dependencies and business requirements are not up to date. The underlying thought processes and risk management is lost. |

| Documentation of the Incident | A chronological issue log containing all activities and decisions is created contemporaneously during the DR activities. It helps to explain what happened in audits and inspections and to justify decisions taken. | The absence of preliminary documentation potentially results in audit findings, leading to a subsequent initiative to generate this documentation retrospectively. However, this is an extraordinarily challenging task, as relevant information is no longer accessible. |

| Processes | Interim processes and supporting templates are created by the quality organization and provided via a cloud storage provider. Training is done virtually, and attendance is recorded manually. | Interim processes are not created as the organization expects to have their SOPs available again soon. In the meantime, recovery activities are performed without established processes. Speed is valued higher than following a process. |

| Data Integrity | A task force was created to ensure appropriate handling of the paper records throughout the entire data life cycle and develop a strategy to integrate the data once the IT system is available again. | Data and records are captured, processed, used, and documented without structure. When relevant systems are available again, there is no concept for data reintegration. Some of the resulting data integrity issues become impossible to resolve. |

Every disaster is unique, and every organization needs to define its strategy and plans. The measures and controls described in this hypothetical case study may not be suitable for every organization. This case study provides a realistic disaster scenario and demonstrates the value of being prepared and having appropriate plans.

The internal audit program ensures regular reviews of business continuity and DR preparedness and compliance with company expectations. In our scenario, this was the case, and these plans were created using critical thinking that accepts that disasters will strike at some point in time.

For our hypothetical company, we can state that they were very well prepared and decisive. They did not simply focus on IT DR but had roles and responsibilities, priorities, and tasks that were planned beyond what was needed. This significantly contributed to getting the situation under control.