Business Continuity Planning to Prevent Drug Shortages

As noted in the ISPE Drug Shortages Prevention Plan,

While powerful, business continuity planning is not always leveraged optimally for preventing drug shortages because it can be difficult to initiate and maintain, particularly when future supply challenges may be unknown or unpredictable, and because it can require a significant investment of money, personnel, training, and other resources. However, over the lifespan of any company, unexpected challenges will inevitably surface. The COVID-19 pandemic is the most illustrative example of our times regarding how significant business continuity planning may be to ensuring uninterrupted supply of critical medicines, as the entire pharmaceutical industry has been challenged by both unprecedented demand and supply constraints globally.

It is understandable how immediate operations necessary to maintain routine supply to the market may be prioritized over proactive measures, which may never be needed or needed in the way that was originally anticipated. Yet it remains essential that pharmaceutical industry leaders pursue strategic approaches for business continuity planning because drug shortages may devastatingly impact patients and their families, as shown in the recent ISPE Drug Shortages Webinar, which described one pediatric cancer patient’s challenges from multiple drug shortages.2

In recent years, large-scale events have motivated governments, health authorities, and patients to focus on the reasons behind supply disruptions. While many root causes are being explored, some markets are prioritizing business continuity planning for the prevention of drug shortages and making these plans a requirement in certain cases.3, 4 Any procedures established to meet these new requirements should be developed with sufficient flexibility to accommodate appropriate evolution of business continuity planning because the risks of today may not be the risks of tomorrow.

Approaches to Business Continuity Planning

The guidance presented in this article is intended to assist pharmaceutical leaders in striking the right balance between critical patient needs and the business investment for drug shortage prevention measures. In general, the concepts described herein apply to all types of pharmaceutical products, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), finished drugs, biologics, vaccines, medical devices, and combination products.

There are a number of excellent resources for business continuity planning. Notably, the ICH Guideline for Quality Risk Management Q95 serves as an important resource document for existing practices, standards, and guidelines within the pharmaceutical industry. As such, ICH Q9 concepts and terminology will be used throughout this overview.

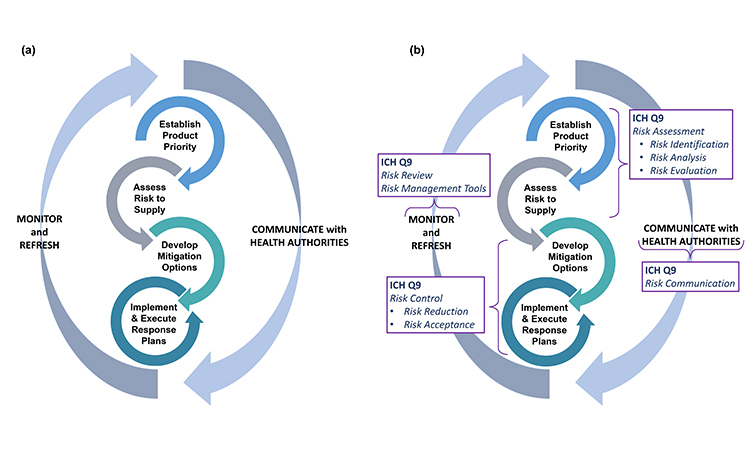

At the outset of pursuing robust business continuity planning for preventing drug shortages, it is important to recognize this is not a one-time event. Rather, the four primary activities in business continuity planning—establishing product priority, evaluating risk to supply, developing mitigation options and agility strategy, and implementing response plans—will need to be revisited and adjusted as the product portfolio and business dynamics change over time (Figure 1). Therefore, companies should develop programs to support an ongoing refresh of their business continuity plans.

Generally, the four stages of business continuity planning will proceed in the order shown in Figure 1; however, as patient needs develop or business or regulatory landscapes change, it may be appropriate to make targeted adjustments within any one of the four stages to ensure the best outcomes.

In each of the four stages, a strong partnership between functional areas within a company will be required for success. The functional areas typically involved in these activities are as follows:

- Customer relations

- External business partnerships

- Legal

- Manufacturing

- Medical affairs

- Procurement

- Quality

- Regulatory affairs

- Sales and marketing

- Supply chain

- Technical/manufacturing operations

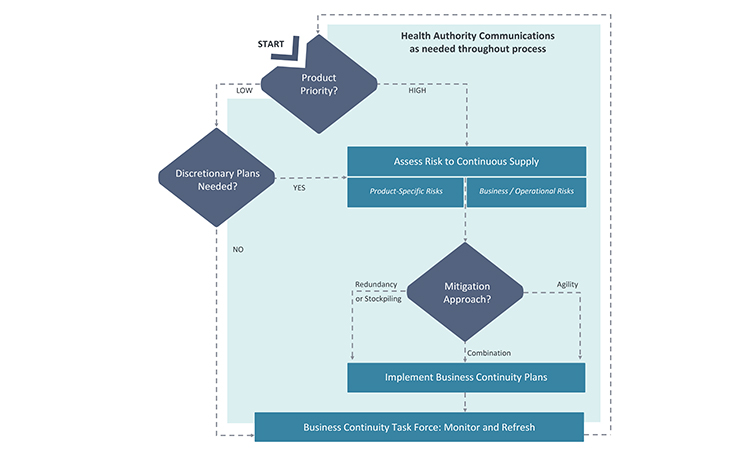

Because many issues and decisions related to business continuity planning will be best addressed after input is considered from multiple functional areas, it is equally important to formally designate a business continuity planning team leader who will have the authority to exercise decisions on behalf of all. Figure 2 illustrates the key stages and decision points for business planning discussed in this article.

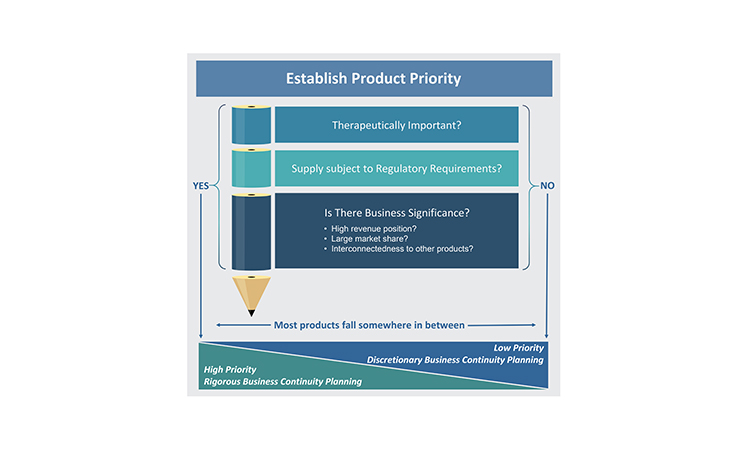

Establishing Product Priority

A foundational activity for business continuity planning is determining the priority of products. Not all products merit the same level of business continuity planning because the impact of supply disruptions is not equal for all products. Considering product priority becomes even more important when the resources required to develop business continuity plans may be constrained. The relative priority of each product will be more reliable if it has been determined by evaluating products individually, as well as across the portfolio of products for which the company is the marketing authorization holder (MAH). This is because there may be important connections between products, often business related, which can influence the priority of an individual product.

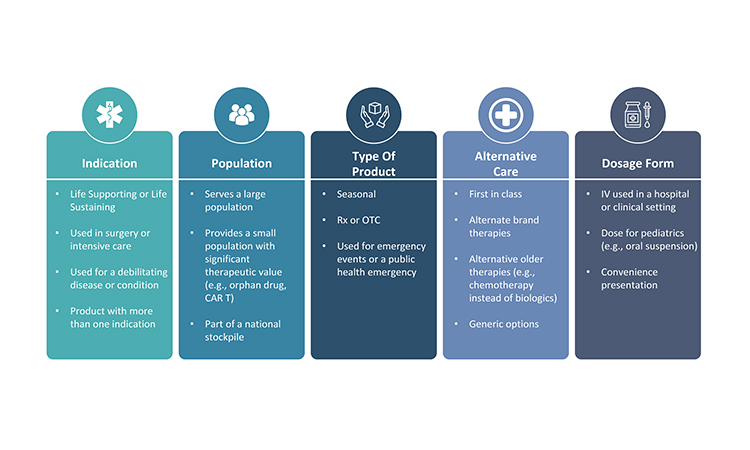

Three perspectives primarily drive prioritization of products: therapeutic importance, regulatory requirements, and business significance. Because of the numerous perspectives that must be considered within these three areas when establishing the product priority, the evaluation of priority is best completed as a cross-functional activity and experts in the business areas listed previously should be consulted.

Therapeutic Importance

The medical significance of a product for patients is the most significant consideration when determining that product’s overall priority. There are several ways to differentiate the therapeutic importance of a product (Figure 3). Applying one therapeutic assessment globally is usually not sufficient because a product may have different therapeutic value across various markets. Additionally, within or across markets, each dosage form and strength within a product family may not always have the same medical priority. Sometimes, a specific dosage form and strength is developed to provide convenience to the health provider or patient and, as a result, its unavailability may not be as impactful as shortages of other dosage forms and strengths.

Regulatory Requirements

Health authorities (also known as national competent authorities) and health organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), can influence product priority significantly through their definitions of what products may be critical, essential, or life-saving for patients in certain markets. They may also designate medically significant products through a set of criteria or through a list of products. For example, the WHO has long maintained an Essential Medicines List.6 Additionally, governments may establish incentives to prioritize products manufactured in a certain market. Typically, health authorities have higher expectations for risk management and business continuity planning for products deemed to be more significant in their market(s).

Currently, there is no harmonized definition across markets regarding what products are significant to the patients.7, 8 As a result, it is imperative that pharmaceutical companies have insight into the definitions or lists applicable for the markets where their products are sold, and which products may be assigned to a national stockpile. Notably, the priority may be dynamic in a market. For example, in a large-scale event, a product that is valuable for emergency use could rapidly become essential and in high demand.

In addition to considering all regulations and governmental expectations when assessing the priority of a product in each market, it is important for companies to maintain constructive interactions with health authorities.9 This will ensure that a company is able to develop a strategic approach to meet requirements across all markets and be poised to engage with the health authorities prior to or at the outset of any significant supply disruption or emergency. Early communication on drug supply challenges, preferably before supply disruptions occur, will maximize the assistance the health authorities may be able to provide to mitigate or prevent a drug shortage.

Business Significance

Business significance of a product should be assessed both from the perspective of the overall revenue position for the company as well as the market share of the product. If a product is essential for a company’s revenues, there may be no financial tolerance to have product supply unavailable for even a day. On the other end of the spectrum, a product might be sold in very low volume and manufactured only once or twice per year. Beyond failure-to-supply costs, which may be written into supply agreements, a supply gap for a low-volume product may have minimal patient impact or business significance. However, even an absence of a small-volume product can create significant challenges for patients who may rely on it, which could then generate business challenge for a company if the health care provider or patient reaction to the absence of product generates unfavorable publicity and impacts the overall reputation of the company.

A market share analysis is an important activity to complete when determining business significance. It should include an analysis of how much market share the company holds for the product, as well as how interconnected the competing suppliers may be to the manufacturing nodes. Generally, if the market for a specific product is divided across at least three manufacturers,10 a supply disruption from one manufacturer may not make a significant difference to the overall market. However, if the market share is divided unevenly and the manufacturer experiencing the supply disruption contributes significantly to the overall industry-wide inventory, the disruption may drive an industry-wide shortage and competitors may have insufficient capacity to increase manufacturing to address the supply gap. Additionally, a product may be a higher priority if any risks to supply would likely impact multiple suppliers (e.g., all companies use the same raw material supplier), and very quickly create an industry-wide gap.

Lastly, connections between products, either within the portfolio of one company (i.e., one MAH holder) or connections with a partner company, may need to be considered when establishing the business significance for each product. One product may be interdependent with other products due to marketing, regulatory quality, or manufacturing supply requirements or strategies. Depending on the nature of the connection, a product that may otherwise be of lower priority may become more significant because interruption in its supply may impact other products the company markets or the company’s partnerships with other companies.

Setting Business Continuity Planning Target Levels

As noted earlier, the appropriate level of business continuity planning will vary by product. For the purposes of establishing a target level of business continuity planning, all of the perspectives described previously will contribute to the final priority categorization. Low-priority products do not typically merit rigorous business continuity planning activities, but the activities may be completed on a discretionary basis based on the company’s goals or preferences. For products that have priority from any of the three perspectives of therapeutic importance, regulatory requirements, or business significance, companies will need to apply an appropriate level of rigor to the business continuity planning activities, based on the perspectives driving the priority (Figure 4).

Assessing Risk to Supply

Once the product priority is established for a product, the company can assess the risks to supply with a better gauge for the potential level of impact of any identified risks. The key learnings from establishing product priority should be considered during the risk assessment process.

Table 1 shows typical areas to consider during a risk assessment for the purposes of preventing shortages. The areas listed are not exhaustive and may not be applicable to every product or company. Each company will need to determine what may best be included in their assessment and should address any company-specific issues or perspectives. Risk assessment activities may not need to be as comprehensive for low-priority products, particularly when any correlating supply disruption may have minimal patient impact.

| Area of Focus | Risk Assessment Considerations |

|---|---|

| Product |

|

| Supply |

|

| Logistics |

|

| Patients |

|

| Environment |

|

The assessment of areas of potential risk should address the fundamental questions posed in ICH Q9:5

- What might go wrong?

- What is the probability it will go wrong?

- What are the consequences?

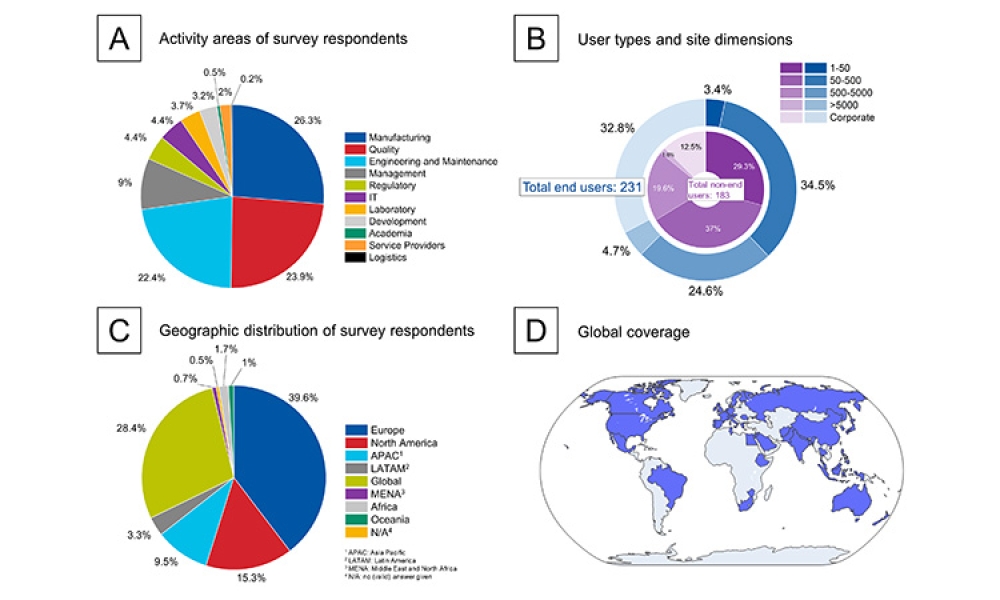

An informal survey of ISPE membership has indicated that companies use a wide range of off-the-shelf and custom-designed risk assessment procedures, tools, and technology. ICH Q9 Annex I provides an overview of common tools for identifying what might go wrong and what is the probability it will go wrong. Table 21, 5, 9–17 lists other valuable guidance resources available to assist with the assessment of risk in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

| Organization | Resource | Year |

|---|---|---|

| ISPE | How to Engage with Health Authorities to Mitigate and Prevent Drug Shortage9 | 2020 |

| FDA* | Drug Shortages: Root Causes and Potential Solutions11 | 2019 |

| EMA | Guidance on Detection and Notification of Shortages of Medicinal Products for Marketing Authorisation Holders (MAHs) in the Union (EEA)12 | 2019 |

| ISO | ISO 14971:2019 Medical Devices—Application of Risk Management to Medical Devices13 | 2019 |

| WHO | Medicines Shortages10 | 2016 |

| WHO | Technical Consultation on Preventing and Managing Global Stock Outs of Medicines14 | 2015 |

| ISPE | Drug Shortage Assessment and Prevention Tool15 | 2015 |

| ISPE | Drug Shortage Prevention Plan1 | 2014 |

| PDA | Risk-Based Approach for Prevention and Management of Drug Shortages16 | 2014 |

| ICH | ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Pharmaceutical Quality System Q1017 | 2008 |

| ICH | ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Quality Risk Management Q95 | 2005 |

*At the time of publication of this article, a new guidance from the FDA regarding risk management plans to mitigate potential for drug shortages was anticipated, but not yet available.

Risk assessments generally evaluate risks to (a) the product, (b) business systems, and (c) operations, and assessments of these three areas may be completed either individually or as a combination activity. When business continuity planning is done for only one area (products, business systems, or operations), the preventive measures may fall woefully short because product supply, business systems, and operations can all be disrupted simultaneously, such as in large-scale events (e.g., hurricanes, earthquakes, pandemics).

Beyond evaluating manufacturing reliability and quality maturity, business continuity planning to avoid drug shortages may benefit from integration with any governance, risk management, and compliance (GRC) or enterprise risk management (ERM) activities already in place for the company. For example, regarding risk to operations, the transformative nature of the COVID-19 pandemic may increase the importance of completing financial viability assessments of business partners, with consideration paid to not only primary business partners but also secondary and tertiary business partners. If a company does not have a formal GRC or ERM program, industry experts and software are available provide guidance suited to the needs of the organization.18, 19,20

Mitigation Options

The outcome of assessing risk to supply should be a road map of the key risks for the products, business systems, and operations to drive the selection of an appropriate business continuity approach.

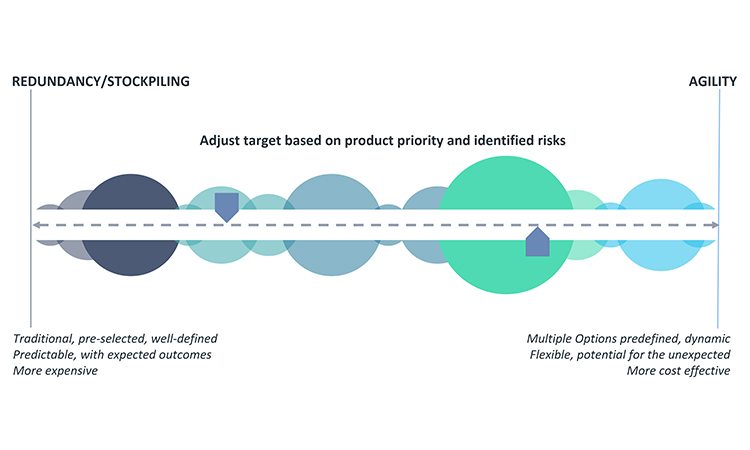

A robust response plan should include both traditional mitigation options, such as redundancy of operations or increased inventory for safety stock, and agility strategy. Agility, as defined herein, is applied in the absence of an immediate back-up facility or inventory stockpile and should enable quick operational reactions to ensure resiliency for continued supply. It requires advanced, forward thinking and preparation to be successful. A well-designed agility strategy can be equally successful as redundancy; however, because agility strategy is by nature infrequently practiced, if it all, there may be some unexpected variation in the outcomes when activated. An appropriate blend of redundancy and agility will typically provide the best resiliency for continued supply. Figure 5 provides insight into the key considerations when selecting the best target on the business continuity planning options spectrum.

Securing backup facilities or materials for pharmaceutical production or stockpiling inventory are longstanding redundancy options to ensure product supply. Although redundancy is well defined and generates expected results, it is costly due to necessary operational overhead. Unexpected complexity may also develop when a company maintains additional facilities, sources of supply, or inventory. Additionally, an adequate number of trained staff and practice runs for back-up operations are necessary to ensure a successful and timely transition to the redundant option, when needed. In some cases, limitations on the number of suppliers or raw material sources mean that redundant facilities or sources of supply are very difficult or impossible to achieve.

Given the implementation challenges or significant investment required to achieve redundancy or stockpiling, they are not always the best options for the manufacturing of every product or every step of manufacture of an individual product. For example, redundancy or stockpiling may not be appropriate for products that are deemed low priority for business continuity planning or products that involve few supply chain risks. Quite often, the decision for the best approach will require input from the various business areas listed earlier (customer relations, external business partnerships, legal, manufacturing, and so on). Because options analysis can quickly become complex, tools such as a decision-matrix method (e.g., Pugh matrix)21,22 may help to guide selection of the best business continuity planning approach.

An important financial perspective to consider for business continuity plan decisions is that, as a general rule, it is better to decrease the level of bound capital along the supply chain from raw materials to API to bulk to the finished goods level because this may decrease the financial impact of the business continuity plan. Increasing inventory of raw materials, API, etc., at the earlier nodes of the supply chain will typically ensure lower, more efficient levels of finished product inventory. It is usually most cost-effective to have a second source for raw materials, excipients, and APIs and only stockpile the finished goods to the level required to meet the marketed forecast. Idle capacity cost should also be considered in the overall investment calculation during the establishment of a contingency plan.

Once redundancy and stockpiling decisions are made, operational agility will need to be developed to offset remaining risk for holistic business continuity planning. Agility requires a company to establish practices and processes to ensure they can address issues when they have occurred. Excelling in agility will allow a manufacturer to quickly pivot operations to maintain supply, such as increasing production or using alternative operations or materials to maintain product supply. Six Sigma23 methodology may be helpful in evaluating and establishing appropriate agility approaches.

Key areas for agility strategy are supply chain, quality, strategic processes, business relationships, technology, regulatory, and metrics. The following are examples of how agility may be achieved in these areas.

- Supply chain:

- Advance thinking about potentially appropriate alternate suppliers (e.g., for raw materials, API, or finished product) can give a company a head start when faced with how to rapidly work with an alternate supplier that is not registered. Robust due diligence activities and well-maintained vendor qualification programs and supplier arrangements are recommended, as they may provide invaluable insights about timely and viable options amid an unexpected supply interruption.

- Companies that can quickly and completely understand the interconnectedness of a product and operations with other products and end markets have superior strategic options to redirect inventory to address market-specific supply disruptions.

- Diversification of suppliers may ensure continuous supply. There are signs that a shifting manufacturing footprint may be on the horizon, particularly due to the impact of COVID-19 on the pharma industry.24, 25

- Quality:

- Quality failures are the root cause for a significant number of drug shortages;11, 26 therefore, it is particularly important to ensure a robust pharmaceutical quality system (PQS)17 across the life cycle of a product.

- A mature PQS—particularly in the areas of change management, monitoring, nonconformance investigations, corrective and preventive actions, complaint handling, and knowledge management—should identify early any issues that may impact continuous pharmaceutical supply, and this allows companies to implement appropriate and timely corrective actions to either mitigate or prevent a drug shortage.

- Lessons learned from regulatory inspections should provide opportunities for continual quality improvement.

- Strategic process development and maintenance:

- When developing manufacturing operations, it may be advantageous to group products with similar excipients to facilitate quick manufacturing switch outs. Having the ability to quickly ramp up one set of products and ramp down others could help companies mitigate a potential shortage situation.

- Challenging the system or operational practices periodically, based on lessons learned or other company experiences, can proactively identify new risks.

- Business relationships:

- Developing strong relationships with suppliers and contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) to understand issues early is invaluable in ensuring the best outcomes for potential or actual supply disruptions.

- Having the ability to quickly start manufacture of a product at a CMO through contracts, foundational qualification work, and training (often referred to as a warm start26) is an agile version of redundancy.

- Companies may want to establish relationships with competitors, so they may partner during significant supply disruptions to temporarily provide patients with an alternate source of supply.

- Technology:

- It can be challenging to use new technologies (e.g., continuous manufacturing) or an alternate type of existing technology (as described in scale-up and post-approval changes [SUPAC] guidance27, 28, 29, 30, 31 for existing products. However, completing foundational development work for new or alternate technology before shortage event occurs may give a company a shorter runway for restart and may help the company adjust to increased demand.

- Regulatory:

- A well-planned regulatory strategy for registration dossiers may be a powerful way to mitigate or prevent drug shortages. As an example, ICH Q12 (Technical and Regulatory Considerations for Pharmaceutical Product Lifecycle Management) 32 describes post-approval change management protocols (PACMPs) for registrations that may potentially alleviate post-approval change requirements. With the appropriate level of process and product understanding, PACMPs may be instrumental in ensuring continuous supply. Therefore, investing in upfront development and regulatory work for agility purposes can be foundational to success.

- Well-developed practices and procedures for engaging health authorities in advance of supply disruptions may help companies mitigate or prevent drug shortages because with early enough insight into an event that may disrupt drug supply, regulators may be able to provide pivotal assistance to help the company address the issue.

- Metrics:

- Metrics to assess agility may or may not be needed and should be established as appropriate on a case--by-case basis. That said, traditional metrics are very valuable and will often help companies know when agility strategy may need to be employed. Traditional metrics closely linked to drug shortage identification and prevention are quality measures and demand forecasting. See the ISPE Drug Shortage Prevention Plan 1 for a more in-depth discussion of important metrics.

- Companies may want to establish a target timeline for transitioning to alternate supply options defined in business continuity plans. This may help companies better understand the overall impact of such transitions and whether predefined mitigation will be sufficient to address a supply disruption event.

Implementing, Monitoring, and Refreshing Response Plans

After the mitigation options and agility strategy are determined, the business continuity plan should be summarized and communicated across the company. Communication tools should include risk control documentation. Additionally, there may be a need to prioritize the implementation of the business continuity plans if multiple plans are established simultaneously.

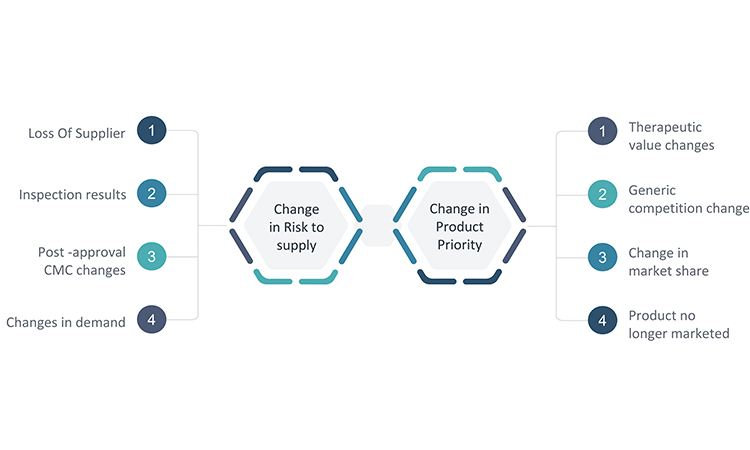

The completion of the business continuity plan and communication of it are certainly noteworthy milestones to celebrate, but they are not the last steps. As noted earlier, circumstances for product supply may change over time, and these changes may impact the outcome of any of the business continuity activities described in the plans. As a result, planning is not a one-time project. However, companies with larger portfolios of products or limited staff may find it unsustainable to routinely reevaluate product priority, supply risks, and the resulting product response plan for each product. Therefore, it is essential to establish a process for a periodic review of changes in circumstances that may impact the risk outlook for supply of one or more products and merit a change to the established response plan. Though this process may vary by company, it is important to develop an event-based trigger to prompt interim reviews. Some key triggers are presented in Figure 6.

Because changes in circumstances may occur in many areas of the business, convening a multifunctional business continuity task force for periodic reviews of potential changes may provide the best opportunity to identify where modifications to a response plan may be warranted. The functional areas listed earlier in the article should be considered when assigning team members to a business continuity task force.

It is important to select key metrics such as demand forecast, supply metrics, capacity, and inspection results that can provide early warnings of potential issues, and develop a plan for how the business continuity task force will monitor these metrics. Additionally, insight into key changes for each area will be needed. Processes should be established in each of the functional areas for how to escalate changes that may have significance to the business continuity plans and are therefore important for the task force to review. The processes should leverage existing systems, such as the quality change control process, for maximum efficiency and effectiveness.

After the periodic analysis is complete, a plan for refreshing impacted response plans should be developed. Additionally, the status of implementation of all business continuity plans and related updates should be monitored by the business continuity task force.

Lastly, and very importantly, any use of established business continuity plans to address an unexpected supply disruption will present an opportunity for evaluating how well the plans worked and if any adjustments should be made. In the absence of actual events, the business continuity plans may also be challenged with announced or unannounced practice runs. The business continuity task force should lead efforts to execute or challenge the business continuity plans and to evaluate the resulting lessons learned.

Health Authority Communications

Health authority interactions and communications are an identified component in the quality risk management process in ICH Q9 and may occur at any point during the different stages of business continuity planning or execution. With respect to ensuring continuity of drug supply, it is important to recognize that regulations are in place to ensure the safety, efficacy, and quality of pharmaceutical products. However, it may be riskier for patients to go without a drug, due to supply disruptions, than to use a drug that does not meet all regulatory provisions. Sometimes, the issue driving the supply disruption will have little or no bearing on the safety, efficacy, or quality of the product, or the issue may be addressed in an innovative way that is not covered by the registered application. Therefore, it is important that MAHs consider all options to achieve responsible regulatory compliance that keeps the benefit/risk profile of the patient at the forefront, and interact candidly with health authorities to determine the most appropriate path forward during challenging circumstances.

Conclusion

This article summarizes key stages and decision points for successful business continuity planning to mitigate and prevent drug shortages, and the foundational concepts described are aligned with ICH Q9 guideline, Quality Risk Management.5 The approach was developed from across company experiences and has benefited from preliminary learnings from the COVID-19 pandemic. It will be reviewed and updated, if required, based on further learnings emerging from industry interactions and regulatory feedback.

Each drug shortage event presents unique challenges and opportunities for improvement, and the events related to COVID-19 are no exception. One of the many outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic has been that companies have needed to rely on business continuity planning to be more flexible and sharpen their focus on ways to ensure continuous supply of critical medicines. When we overcome these difficult times, it will be important to understand which business continuity measures worked well during this enormous, global event and which did not. There will also be an important opportunity to identify which manufacturing or business practices developed during the pandemic may be appropriate to implement routinely for greater effectiveness in the supply chain overall. Exciting new directions and enduring solutions for preventing and mitigating drug shortages may be achieved, and this constant evolution in the business continuity planning space should always be embraced.

The ISPE Drug Shortages Team is a team of multidisciplinary experts who seek to assist ISPE membership, industry, and regulatory collaborations to reduce drug shortages globally through technology, quality, and manufacturing innovation and regulatory compliance. This team is actively monitoring developments related to drug shortages and is available to respond to any associated questions. We welcome input on best practices to support the continuity of supply and decision-making regarding actual or potential drug shortages.

Larger versions of the figures in this article are available here:

Business Continuity Planning to Prevent Drug Shortages figures

Acknowledgment

The ISPE Drug Shortage Initiative Team collectively developed the content for this article and special recognition is extended to the following contributors:

James Canterbury, Principal, Ernst & Young LLP, Iselin, NJ

Dawn Culp, BS, Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., Berkeley Heights, NJ

Nasir Egal, PhD, Sanofi, Washington, DC

Erin R. Fox, PharmD, University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, UT

Jean Francois Duliere, Pharmaceutical Senior Expert and Consultant, Paris, France

Emma Harrington, Moderna, Norwood, MA,

Drishya Nair, MS, Ernst & Young US LLP, Iselin, NJ

Terrance Ocheltree, PhD, RPh, Corium, Inc., Libertyville, IL

Christopher J. Potter, CMC Pharmaceutical Consultant, Marlborough, UK

Thomas Zimmer, PhD, ISPE Vice President, European Operations , Harxheim, GER